September 2015

Michael Botticelli

Director of National Drug Control Policy

September is National Alcohol and Drug Addiction Recovery Month, and during this month, we celebrate the stories of people in recovery. Speaking about one’s recovery journey helps erase the shame and stigma that often attach to individuals with substance use disorders. Like myself, Gene (whose story is below) is one of millions of Americans in recovery, and I am grateful to him for sharing his story. Gene’s recovery is especially instructive in the midst of the Nation’s opioid crisis because it illustrates that recovery from opioid use disorders is possible.

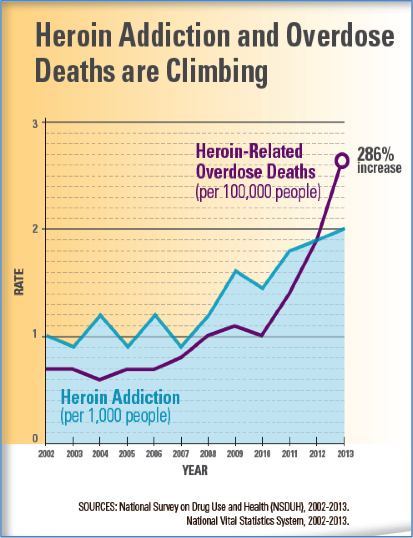

Opioid use disorders and overdose deaths continue to ravage families and communities across the Nation. Driven in large part by the surge in nonmedical use of prescription opioids (narcotic painkillers),  overdose has become the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., surpassing the number of deaths due to motor vehicle crashes and firearms.

overdose has become the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., surpassing the number of deaths due to motor vehicle crashes and firearms.

Overdose has become the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., surpassing motor vehicle accidents.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that in 2013, 44 people in the United States died every day from an overdose of prescription opioids that amounts to 16,235 deaths in a single year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). However, we are not powerless in the face of the opioid epidemic. We know how to prevent opioid use disorders – and how to save lives from overdose.

Gene, a 44-year-old former semi-professional football player who worked at the Pentagon for 18 years, had much going for him. He had two sons, a daughter, and a long-term girlfriend. Fellow workers looked up to him and often sought his counsel. However, his life began to take a marked turn for the worse in 2005, when he was prescribed pain medication for degenerative conditions in his hips and back related to football injuries and his use of steroids as a player. Gene became addicted to the pain medication. Soon the mortgage, utilities, and other bills began going unpaid, and there was not enough money for groceries. The resources that once supported Gene and his family were now being siphoned off to purchase the drugs he needed to function. Over time, he transitioned from prescription pain pills to heroin, another opioid. Gene lost his home and his family.

In February 2015, Gene sought treatment, last using substances on February 15th. Shortly after beginning his recovery journey, Gene became suicidal, feeling hopeless and alone. He was admitted to a psychiatric unit at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, where he was diagnosed with depression, hypertension, and a soft tissue cancer near the joints damaged by his football injuries and steroid use.

"I look at taking Suboxone like taking medicine for high blood pressure or insulin for diabetes. It's a medicine that treats a disease. It's a medicine that helps provide you with the confidence to live life on life's terms. Untreated, the disease of addiction is just as deadly as cancer or heart disease."

-Gene

From the psychiatric unit, Gene was transferred to the Johns Hopkins Hospital Broadway Center for Addiction. A component of his treatment there was the Collaborative Opioid Prescribing program (CoOP), where he was linked to a primary care doctor who prescribed buprenorphine for his opioid use disorder. His Suboxone (buprenorphine) prescription has removed his cravings and the sickness that would come as he went into withdrawal, making it possible for him to participate in treatment and begin the recovery process.

Currently, Gene is in a wheelchair awaiting a combined hip replacement and back surgery that will permit him to walk again. While he must confront chronic pain without the use of prescription pain medications, his life is full of hope and promise. His children have returned and he is eager to continue in his recovery, attending eight treatment groups per week and regularly attending mutual aid groups, even serving as the secretary of one. He also has new tools to help with the chronic pain for which he was initially prescribed opioid medication. Gene has found that prayer, meditation, breathing exercises, and a mobile application allow him to move through and beyond the pain. It no longer controls him. Rather, he manages it. What’s more, his upcoming surgery promises not only renewed mobility, but the prospect of a significant reduction in pain. Today, the future is bright.

Gene has found that prayer, meditation, breathing exercises, and a mobile application allow him to move through and beyond the pain. It no longer controls him. He manages it. What's more, his upcoming surgery promises not only renewed mobility, but the prospect of a significant reduction in pain. Today the future is bright.

Gene’s story provides a window into how the treatment for opioid use disorders can be effectively integrated with a full range of medical, psychiatric, housing, recovery support, and social services—something that was made possible through the CoOP program developed by Dr. Kenneth Stoller at Johns Hopkins (Stoller, K.B., 2015). The CoOP model is one of a growing number of approaches to integrating the treatment of opioid use disorders with primary care, outpatient and residential substance use disorder treatment, recovery support, and other services. An adaptive stepped-care approach that allows services and strategies to be adapted to the changing needs of the patient, the CoOP model is relatively easy to implement and readily scalable. Its goal, said Dr. Stoller, “is to increase the availability, utilization, and efficacy of office-based buprenorphine maintenance.” At a minimum, it requires an opioid treatment program (OTP, sometimes known as a methadone maintenance program) to serve as a hub where counseling and other treatment services are provided, as well as an external office-based physician who can maintain the routine prescribing of buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorders. As illustrated in Gene’s story, the CoOP framework can be enriched through integration with non-SUD services, such as psychiatric, general medical, housing, and social services.

Under this approach, the OTP staff, the physician prescribing buprenorphine through an office-based opioid treatment (OBOT) waiver, and other providers communicate regularly. This ongoing collaboration allows for adjustments to counseling intensity and medication prescribing and dispensing based on the patient’s response to treatment. It also provides OBOT physicians with the support and expertise of the OTP, encouraging the use of their waivers while enhancing quality of care. If the patient begins to use drugs or starts missing counseling sessions, schedules can be intensified, and when necessary, medication dispensing can be shifted from the OBOT to the OTP, allowing for greater control and monitoring. As he or she stabilizes and begins to advance in recovery, counseling intensity can be decreased and medication prescribing shifted back to the physician’s office. When patients are not responding to care, a change in medication from buprenorphine to methadone or a change in setting (e.g., to residential care) can be offered. The table below, furnished by Dr. Stoller, illustrates this.

| Step | Opioid Agonist Medication | Medication Rx or Dispensing Location | Medication Rx or Dispensing Frequency | Counseling Intensity at OTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stable OBOT | Buprenorphine | OBOT | 4 week prescription | Low |

| 2. Intensive OBOT | Buprenorphine | OBOT | 1 week prescription | Intensive |

| 3. Intensive OTP | Buprenorphine | OTP | Daily dispensing | Intensive |

| 4. Methadone OTP | Methadone | OTP | Daily dispensing | Intensive |

We are entering a new era in which the way we provide health care is evolving. There is growing awareness that a substance use disorder is not the result of a personal, family, or community failing, but is a medical condition that can be successfully treated and from which people can and do recover. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), which sets drug policy for the Federal Government, is leading efforts to increase access to treatment and medication-assisted treatment through the use of FDA-approved medications (buprenorphine, methadone, injectable naltrexone, and combination products). In addition, ONDCP has led efforts to increase the number of first responders who carry naloxone, a drug that can reverse a potentially fatal opioid overdose. States are also adopting “Good Samaritan” laws that provide limited immunity from arrest and prosecution for individuals who call first responders when there is an overdose.

The specialty substance abuse disorder treatment, primary care, general medicine, and recovery communities need now, more than ever, to speak and work as one to move the field forward and to educate communities and policy makers.

The Administration released a Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Plan in 2011 which identified a four step approach to preventing prescription drug abuse, to include education of patients and prescribers; expanding state prescription drug monitoring programs; proper disposal of prescription drugs; and enhanced law enforcement efforts to reduce the number of illicit pain clinics. In addition, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has released an Opioid Initiative, and HHS agencies are working with governors across the country to implement the plan.

A few examples of HHS efforts include the release of an Opioid Overdose Toolkit by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). SAMHSA has also awarded grants for states with high per capita rates of treatment admissions for opioid use disorders; the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services is funding Medicaid Health Homes for people with opioid use disorders; and the Health Resources Services Administration is making specialty treatment services available in Federally Qualified Health Centers.

Together, we can turn the corner by mobilizing support for creating the services and systems needed to help more people find pathways from addiction to recovery. By working to educate and inform, we can stem the tide of opioid overdose deaths and welcome those who have found their way back from this disease into our communities. Gene’s story, the CoOP program, and many other efforts across the Nation demonstrate that we can do this.

Join Michael Botticelli on September 17, 2015, for Recovery Month at the White House

Please join me in making sure that those affected by opioid use disorders have access to comprehensive evidence-based services, including the medications that can increase their chances of overcoming this disease and decrease the likelihood of losing their life to overdose.