March 2015

Christine Reilly

Senior Research Director

National Center for Responsible Gaming

The National Center for Responsible Gaming (NCRG), the only private source of funding for research on gambling disorder in the US, makes dissemination of research findings to healthcare providers a top priority. We thank the Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network for this opportunity to summarize research on gambling problems and disorder.

Gambling in the US

An estimated 80 percent of adults in the US gambled in the past year (Welte, Barnes, Wieczorek, Tidwell, & Parker, 2002). Gambling activities include the lottery, casino games, slot machines, video poker, card games, bingo, raffles, and sports betting—from office pools to illegal wagers with bookies.

According to several national surveys, approximately 1 percent of the US general adult population meets diagnostic criteria for a gambling disorder with an additional 2 - 3 percent experiencing some symptoms but not sufficient for a diagnosis (Kessler et al., 2008; Shaffer, Hall, & Vander Bilt, 1999). Despite the great expansion of legalized gambling in the US over the past forty years, the adult prevalence rate of one percent has remained stable in this period (LaPlante & Shaffer, 2007; Reilly, 2008).

Resistance to Treatment

An analysis of two national surveys found that only 5.5 percent of disordered gamblers received professional treatment for gambling problems and only 7.3 percent had attended one or more Gamblers Anonymous meetings (Slutske, 2006).

Researchers are currently investigating the possible reasons for resistance to seeking help and have speculated that the following factors are at play: shame and stigma; lack of awareness that help is available; lack of financial resources; lack of confidence that change is possible; and negative views of available treatments (Suurvali, Hodgins, & Cunningham, 2010).

Importance of Screening

However, 50 percent of disordered gamblers have been in treatment for other psychiatric disorders and in these cases approximately three-quarters of the disorders occurred before the gambling problem (Kessler et al., 2008). This finding led the National Comorbidity Survey Replication to conclude that the onset of a gambling problem could be prevented if clinicians increased monitoring for emerging gambling problems (Kessler et al., 2008).

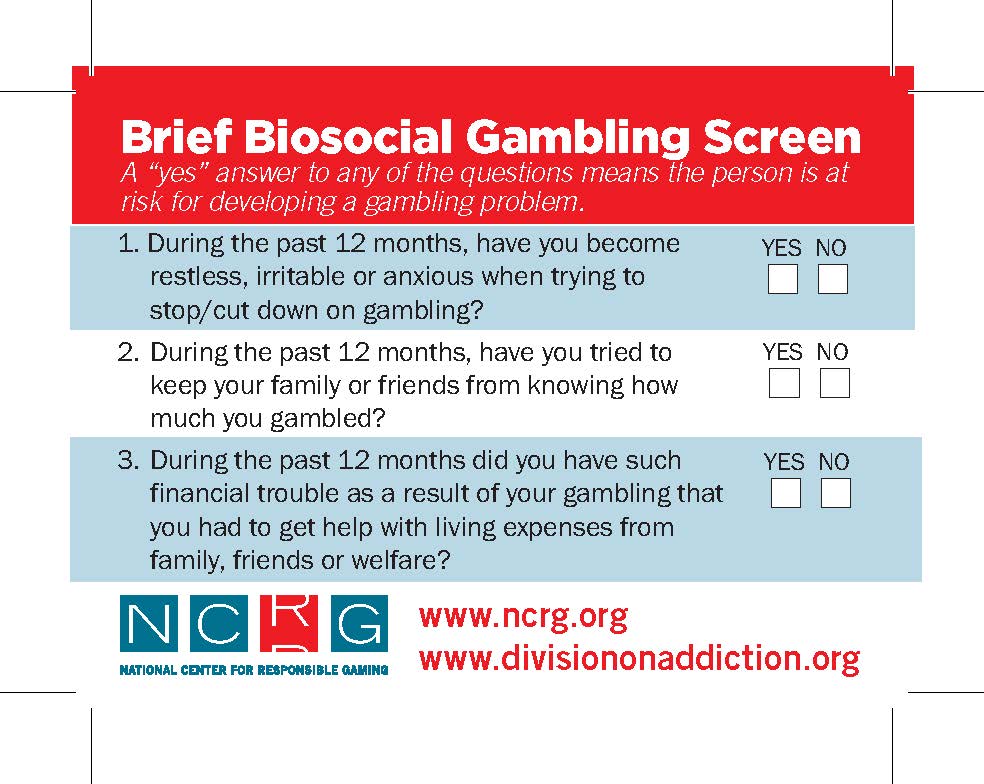

Clinicians are encouraged to use the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS), developed by Harvard Medical School. The three-question BBGS has strong psychometric properties having been developed on the basis of the criteria most endorsed by disordered gamblers in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions, a national survey of 43,000 Americans (Gebauer, LaBrie, & Shaffer, 2010). The BBGS uses a past-year framework, which is important because screening instruments that asks questions about lifetime experiences hold the potential for false positives. (The BBGS is available for free in magnet form from the NCRG. Contact Christine Reilly, [email protected]. The screen is also available online at www.divisiononaddiction.org.)

Clinicians are encouraged to use the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS), developed by Harvard Medical School. The three-question BBGS has strong psychometric properties having been developed on the basis of the criteria most endorsed by disordered gamblers in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions, a national survey of 43,000 Americans (Gebauer, LaBrie, & Shaffer, 2010). The BBGS uses a past-year framework, which is important because screening instruments that asks questions about lifetime experiences hold the potential for false positives. (The BBGS is available for free in magnet form from the NCRG. Contact Christine Reilly, [email protected]. The screen is also available online at www.divisiononaddiction.org.)

Family History

We now have ample scientific evidence that gambling disorder is familial. Genetics plays an important role in the risk of developing a gambling disorder (Comings, 1998) and gambling problems tend to run in families (Black, Monahan, Temkit, & Shaw, 2006). Family history has implications for treatment options as well as assessment. In a study investigating clinical factors associated with treatment outcome with the drugs nalmefene or naltrexone, a positive family history of alcoholism was the factor most robustly associated with a better outcome of reduced problem gambling severity (Grant & Odlaug, 2012).

Treatment and Recovery

The field has yet to establish a treatment standard for gambling disorder, and there is no FDA-approved pharmaceutical specifically for the disorder. However, research has shown that various treatment strategies—especially those used for substance use disorders, such as CBT and Motivational Interviewing—have promise for helping disordered gamblers.

Until a treatment standard is established, clinicians are advised to consider a “cocktail approach” that employs a variety of strategies (Shaffer & Martin, 2011):

Co-occurring Disorders

One of the most important aspects of assessment and treatment planning is to ascertain the presence of co-occurring disorders that might have preceded the gambling problem. According to the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 96.3 percent of individuals with a gambling disorder have or had a co-occurring psychiatric disorder in their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2008). Among these individuals, the co-occurring disorder preceded or emerged simultaneously with the gambling problem 76.5 percent of the time. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders advises that excessive gambling could be the result of a manic episode (bipolar disorder)(American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Consequently, addressing co-occurring disorders is vital to helping disordered gamblers recover.

Relapse

Researchers estimate that as many as 75 percent of disordered gamblers return to gambling shortly after a serious attempt to quit (Hodgins, Currie, el-Guebaly, & Diskin, 2007). Possible reasons for relapse include optimism about winning; need for money; unstructured time or boredom; giving into urges; habit or opportunity; and dealing with negative emotions or situations (Hodgins, 2007; Hodgins & el-Guebaly, 2004). The research suggests there is no quick fix or single treatment model for gambling relapse. Participants in studies most frequently described financial and emotional reasons as important in their decision to quit. Yet, these same factors appear to lead to relapse. These studies reinforce the importance of identifying and avoiding triggers and high-risk situations.

DSM-5: A New Way of Looking at Gambling Disorder

Released in 2013, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders changed the name of the disorder from “Pathological Gambling” to “Gambling Disorder” and reclassified it as an “Addiction” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM-5 also eliminated the criterion, “commits illegal acts,” and lowered the threshold from five to four symptoms for a diagnosis. For more details about the changes in DSM-5, click here to download “From Pathological Gambling to Gambling Disorder: Changes in the DSM-5.”

For more on the latest research on gambling disorder, visit www.ncg.org and follow the NCRG’s blog, Gambling Disorders 360°.

Visit the new ATTC Network Problem Gambling webpage, which features recorded expert-led webinars on many of the topics covered in this article.