By Carole Warshaw, MD, and Gabriela Zapata-Alma, LCSW, CADC

National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Can Have Profound Traumatic Effects and is Pervasive Among People Accessing Treatment Services

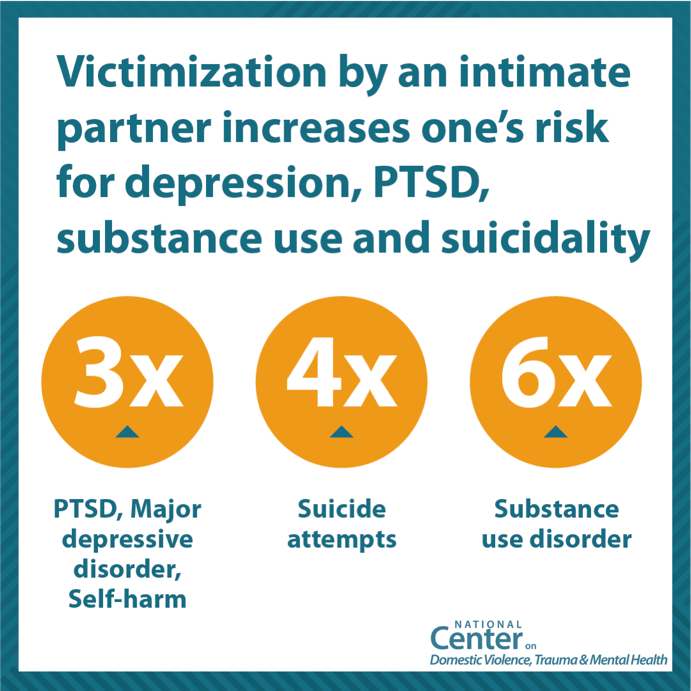

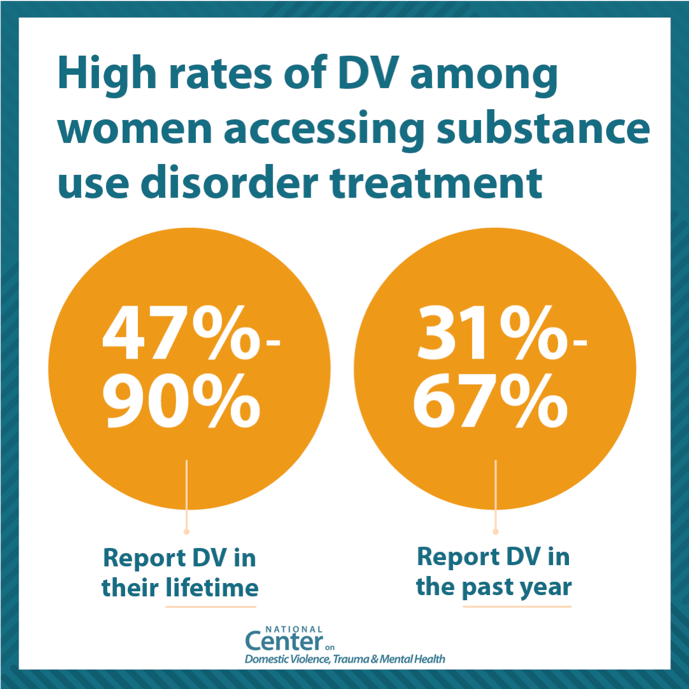

A large body of research demonstrates that experiencing abuse by an intimate partner is associated with a range of behavioral health consequences. Some are the direct results of violence; others are related to the traumatic psychophysiological effects of ongoing abuse. Both clinical and population-based studies indicate that victimization by an intimate partner places people at significantly higher risk for substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, insomnia, chronic pain, and suicide attempts, regardless of whether they have suffered physical injury. In addition, there are high rates of IPV among people accessing services in substance use disorder treatment settings (Warshaw & Zapata-Alma, 2020; Phillips, 2014; Dillon et al., 2013; Nathanson et al., 2012; Trevillion et al., 2012; Howard et al., 2013; Riviera et al., 2015; Warshaw et al., 2009).

Substance Use Coercion: Insidious and Ubiquitous

Less well researched, however, are the ways that people who abuse their partners engage in coercive tactics related to their partner’s substance use as part of a broader pattern of abuse and control – tactics known as substance use coercion. These tactics include deliberately introducing a partner to substances, forcing or coercing a partner to use, interfering with treatment, controlling medication; sabotaging recovery efforts; threatening a partner with withdrawal, and leveraging the stigma associated with substance use to discredit a partner with potential sources of safety and support. Pervasive stigma associated with substance use contributes to the effectiveness of these tactics (Warshaw et al., 2014).

who abuse their partners engage in coercive tactics related to their partner’s substance use as part of a broader pattern of abuse and control – tactics known as substance use coercion. These tactics include deliberately introducing a partner to substances, forcing or coercing a partner to use, interfering with treatment, controlling medication; sabotaging recovery efforts; threatening a partner with withdrawal, and leveraging the stigma associated with substance use to discredit a partner with potential sources of safety and support. Pervasive stigma associated with substance use contributes to the effectiveness of these tactics (Warshaw et al., 2014).

Addressing Substance Use Coercion in Clinical Practice

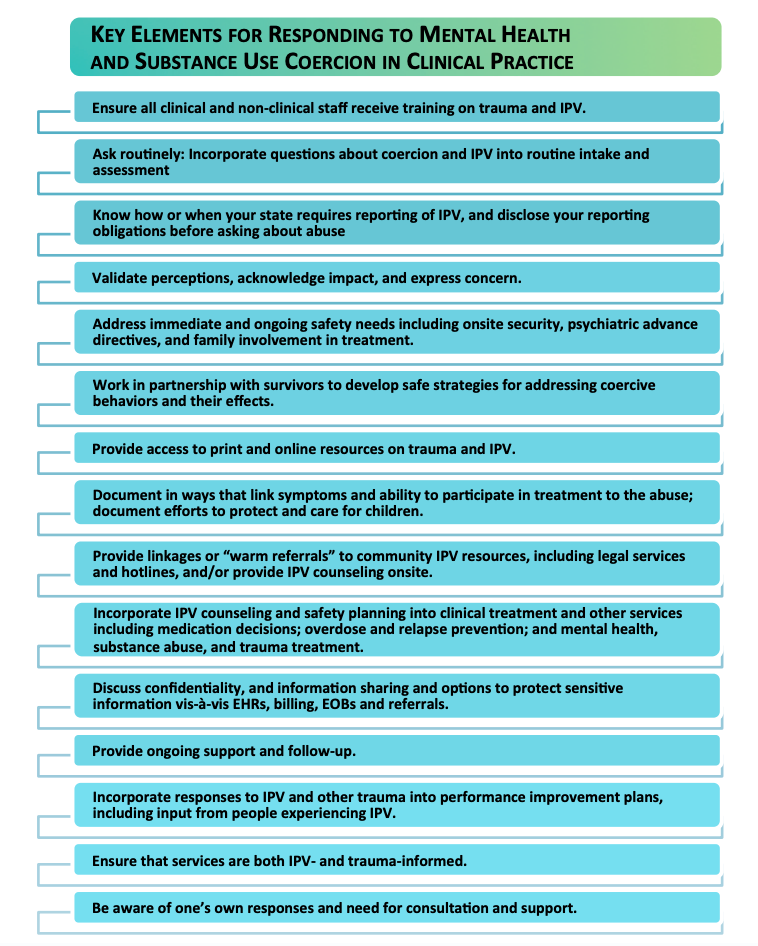

Providing effective treatment for substance use disorders requires an understanding of the factors that led to its development and the circumstances that impact treatment and recovery. In the context of IPV, this means recognizing that in addition to experiencing the traumatic effects of abuse, many survivors experience coercive

tactics specifically related to their use of substances. Thus, routine assessment for substance use coercion and IPV-related trauma, along with specifically tailored counseling, referrals, and treatment are critical to the provision of good clinical care. If your practice is not already set up to respond to IPV, there are a number of steps you can take to prepare. These include ensuring that everyone working in your practice receives training on understanding and responding to IPV, that policies and procedures are in place regarding safety and confidentiality, that written information and resources are available, and that warm referral mechanisms have been established with domestic violence (DV) programs in your community. Consider what level of IPV services you are able to integrate into your existing services and to whom you will link for more in-depth support.

IPV-Informed Programs: Programs that are aware of the dynamics of IPV, substance use disorder, and substance use coercion, and integrate this knowledge into treatment and recovery services. Examples include: cross-training staff, interdisciplinary teams, and referral partnerships.

Collaborative Programs: Programs that have active collaborations across SUD/DV fields. Examples include: offering co-facilitated groups in both settings, active linkages, and co-located services.

Integrated Programs: Programs that offer a full integration of SUD and DV services. Examples include: integrated assessment and service planning, menu of SUD and DV services offered across programs and provided based on survivor’s self-defined needs, and a ‘no wrong door’ approach that offer comprehensive and holistic services for survivors and their families.

How can practitioners build capacity for addressing IPV and Substance Use Coercion in Treatment and Recovery Services

NCDVTMH offers many resources and services to support practitioners and organizations in increasing their responsiveness to the needs of survivors and their families. Some highlighted resources include:

NCDVTMH offers many resources and services to support practitioners and organizations in increasing their responsiveness to the needs of survivors and their families. Some highlighted resources include:

Correspondence should be addressed to Carole Warshaw, MD, and Gabriela Zapata-Alma, LCSW, CADC.

References

Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, and Rahman S. (2013). Mental and Physical Health and

Intimate Partner Violence against Women: A Review of the Literature. International

Journal of Family Medicine, 1-15. doi:10.1155/2013/313909.

Howard, L. M., Oram, S., Galley, H., Trevillion, K., & Feder, G. (2013). Domestic violence

and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS

medicine, 10(5), e1001452.

Nathanson, A. M., Shorey, R. C., Tirone, V., & Rhatigan, D. L. (2012). The prevalence of

mental health disorders in a community sample of female victims of intimate partner

violence. Partner abuse, 3(1), 59.

Phillips H. (2014). Current Evidence: Intimate Partner Violence, Trauma-Related Mental

Health Conditions & Chronic Illness. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma,

and Mental Health.

Rivera, E. A., Phillips, H., Warshaw, C., Lyon, E., Bland, P. J., Kaewken, O. (2015). An

applied research paper on the relationship between intimate partner violence and

substance use. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health.

Trevillion, K., Oram, S., Feder, G., & Howard, L. M. (2012). Experiences of domestic

violence and mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS one,

7(12), e51740.

Warshaw, C. & Zapata-Alma, G.A. (2020). Mental Health Treatment in the Context of

Intimate Partner Violence. In (R. Geffner, J.W. White, K. Hamberger, A. Rosenbaum,

V. Vaughan-Eden, V. I. Vieth, Eds; J. Langhinrichsen-Rohling, G. Tinney, S.M.

Wagers, L. K. Hamberger, A. Rosenbaum Section Eds.). Handbook of Interpersonal

Violence Across the Lifespan: A Project of the National Partnership to End

Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan (NPEIV). New York: Springer International

Publishing.

Warshaw, C., & Tinnon, E. (2018). Coercion Related to Mental Health and Substance

Use in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence: A Toolkit for Screening, Assessment,

and Brief Counseling in Primary Care and Behavioral Health Settings. National Center

on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health.

Warshaw, C., Brashler, P., and Gill, J. (2009). Mental health consequences of intimate

partner violence. In C. Mitchell and D. Anglin (Eds.), Intimate partner violence: A

health based perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Warshaw, C, Lyon, E, Bland, P, Phillips, H, & Hooper, M. (2014). Mental health and

substance use coercion surveys: report from the National Center on Domestic

Violence, Trauma & Mental Health and the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health and the National

Domestic Violence Hotline.