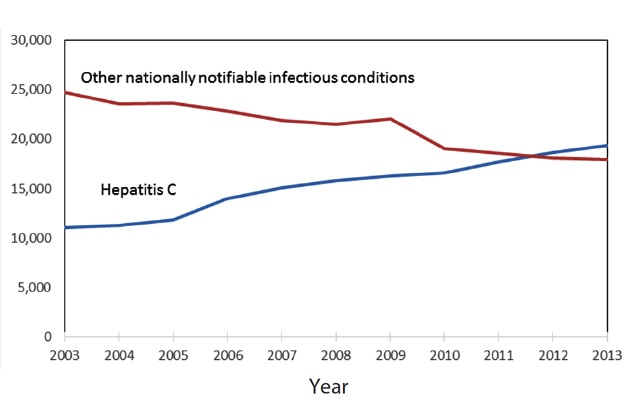

The opioid crisis and associated injection drug use have fueled a dramatic increase in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections among people who inject drugs (PWID). Since 2012, there have been more deaths due to hepatitis C than all 60 of the other reportable infectious diseases combined, including HIV, pneumococcal disease, and tuberculosis (Ly, et al., 2016).

From: Rising Mortality Associated With Hepatitis C Virus in the United States, 2003–2013. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):1287-1288. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw111. Clin Infect Dis | Published by Oxford University Press for the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2016. This work is written by (a) US Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US.

Research from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that the biggest surge in new HCV infections is among young people: between 2004 and 2014, HCV infections increased by 400 percent among people ages 18-29 and 325 percent among 30- to 39-year olds.

Yet many could be cured of HCV and engage in care for substance misuse through an integrated approach to care that includes HCV screening, confirmatory diagnostic testing, evaluation of liver disease, and medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) and HCV under one roof, with co-located HCV and addiction care, says Dr. Lynn E. Taylor.

“We have to tackle the nexus of the opiate crisis and HCV,” says Taylor. “Every overdose can represent five to seven new HCV infections.

Opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are effective places to screen for HCV, but there has to be a clear, low-threshold path to next steps on the cascade to cure. According to the CDC, 50% of reactive HCV antibody results in the U.S. are lost to follow-up, and PWID may face formidable barriers to HCV treatment at the system, provider, and patient level. “With HCV among PWID, the goals are to enhance both individual and public health,” says Taylor. “We work to decrease the time from infection to cure to reduce time of infectivity and thus stem transmission. HCV elimination must be achieved within the framework of enhancing fundamental healthcare for PWID.”

Opioid treatment programs (OTPs) are effective places to screen for HCV, but there has to be a clear, low-threshold path to next steps on the cascade to cure. According to the CDC, 50% of reactive HCV antibody results in the U.S. are lost to follow-up, and PWID may face formidable barriers to HCV treatment at the system, provider, and patient level. “With HCV among PWID, the goals are to enhance both individual and public health,” says Taylor. “We work to decrease the time from infection to cure to reduce time of infectivity and thus stem transmission. HCV elimination must be achieved within the framework of enhancing fundamental healthcare for PWID.”

Taylor is Director of HIV and Viral Hepatitis Services at CODAC Behavioral Healthcare Inc., Rhode Island’s largest non-profit provider of methadone maintenance treatment. There, she oversees a caseload of over 2,000 patients with and at risk for HCV and HIV and runs an on-site HCV clinic at the largest of CODAC’s six sites, CODAC Providence. Taylor is also a primary care physician and buprenorphine prescriber and research professor at the University of Rhode Island, where she serves as Rhode Island site Principal Investigator for an ongoing national research study, Real World Direct Acting Antiviral (DAA) Outcomes Among People Who Inject Drugs: Hepatitis C Real Options (HERO).

In 2013, the FDA approved the drug Sofosbuvir, the first DAA medication for the treatment of HCV that could cure HCV without interferon. Since then, additional DAAs have become available. DAAs are taken orally, have few side effects, and can eliminate the virus in 8 to 12 weeks of treatment. These drugs have revolutionized treatment, making HCV the first virus that is curable through medication, and making HCV elimination possible.

The release of the first DAAs that could lead to Sustained Virological Response (SVR, meaning the virus remains undetected twelve weeks after treatment, equivalent to cure) without interferon inspired the opening of an HCV clinic on-site at CODAC Providence. The clinic has been a one-stop shop since 2014, offering real-time co-located care. Taylor worked at the clinic part-time from 2014 until recently accepting the position of full-time director of HIV and viral hepatitis services, in order to reach patients with and at risk for HIV and viral hepatitis who had difficulty accessing care in traditional settings.

Benefits beyond the Cure:

"We are seeing transformations in people who thought that they would die from HCV,” says Taylor. “With SVR, our patients are motivated to quit smoking and work on alcohol cessation. Relationships are being repaired as feelings of shame and stigma are alleviated. This is turning the field upside down."

The marginalized patient population served at CODAC Providence faces multiple health care disparities: disadvantages in education and employment, unstable housing, frequent interactions with the criminal justice system, and often, under insurance and lack of primary care and dental care. For example, many are Medicaid recipients; in Rhode Island (and other states) this means that there are obstacles to DAA access, as RI Medicaid only provides access to DAAs to patients with advanced liver scarring and has sobriety and prescriber requirements.”

The program goal at CODAC Providence HCV is micro-elimination of HCV among the transmitting population. Taylor and her team aim to ensure that all patients have access to curative HCV treatment, and create a trusting environment to facilitate this. Patients are not denied treatment based on their drug and/or alcohol use.

“The question is not if we will provide treatment, but how,” says Taylor.

One barrier to overcome is patients’ mistrust of healthcare systems in general and at times, in opioid treatment programs in particular.

“We provide compassionate and comprehensive care in a safe place,” says Taylor. “We do not get tox screens as part of HCV care, but work to create an environment in which patients can talk about the details of their injection drug use, how they are injecting, where they are injecting, what they are injecting, and how we can minimize harm, decrease risk of overdose, reduce risk of infectious consequences of injection drug use, and promote fundamental heath,” she explains. “And because almost every patient has a story of feeling discriminated against or shamed in the health care system, we work on building trust, emphasizing to our patients that they are worthy of treatment and that we are present to embrace them and help them to be as healthy as possible.”

Taylor notes that the HCV care cascade has failed to reach PWID in sufficient numbers. Often people are forced to receive treatment for OUD in one place without HCV care, or HCV care at one center without OUD treatment, leading to fragmented care.

“PWID are shuffled around, increasing the likelihood of dropping out of care, or being lost to follow-up,” comments Taylor.

Co-located care reduces the complexity of the HCV cascade and may shorten the time from infection to cure, especially important among the transmitting population. Key aspects of care are delivered on-site, at a single site. Integrated care unites expertise in both HCV and substance use as well as other comorbidities. Co-localization of services may reduce the number of needed appointments and transportation time to reach care.

Co-location can be physical, as in the model described above; colocation can also be virtual.

“Telemedicine employs technological advances to bridge geographic separation between HCV clinician and substance use care facility,” explains Taylor. “Two-way videoconferencing between patient and specialist imports HCV care into locales lacking HCV infrastructure and/or expertise.” Taylor citesAndrew Talal MD’s study of HCV telehealth in New York as a model for expansion, whereby specialty HCV care is brought into a methadone maintenance program to expand access to HCV cure. To date, patients report high rate of acceptability along with high SVR rates.

For Taylor, combining research with work in real-world settings is essential to eliminating HCV.

“We are seeing transformations in people who thought that they would die from HCV,” says Taylor. “With SVR, our patients are motivated to quit smoking and work on alcohol cessation. Relationships are being repaired as feelings of shame and stigma are alleviated. This is turning the field upside down."

The HERO Study:

"The study benefits from guidance from a broad range of stakeholders, including national advocacy and medical organizations, government, clinicians, patients, and industry. Patient input is front and center."

“Determining which strategies are most effective to enhance a simplified care cascade in the DAA era is imperative while ongoing action is taken.”

Taylor is excited about the HERO Study, a five-year research program led by Principal Investigator Alain Litwin, MD, MPH, MS, funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). This project includes eight study sites across the U.S., offering geographic and policy diversity, and examines real-world outcomes of HCV treatment with DAAs among PWID.

HERO is enrolling 750 PWID (injecting within past three months) for a treatment uptake goal of 600 PWID for 12-weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Participants, including those on and not on opioid agonist therapy, are treated at either community health centers (CHC) or methadone maintenance programs. Participants (DAA-naïve, any HCV genotype, any HIV status) are randomized to modified directly observed therapy (mDOT) or patient navigation (PN).

Those randomized to mDOT at methadone clinics receive sofosbuvir/velpatasvir with daily methadone; those at CHC settings video-record themselves taking sofosbuvir/velpatasvir daily using an app called emocha. Participants randomized to PN receive a standardized intervention. Primary outcome is SVR compared between mDOT and PN arms; secondary outcomes include treatment initiation, adherence, completion, resistance, and reinfection after treatment completion. HERO also includes a nested implementation study. Adds Taylor, “The study benefits from guidance from a broad range of stakeholders including national advocacy and medical organizations, government, clinicians, patients, and industry. Patient input is front and center.”

Taylor’s research has included analyses of state and federal policies. A 2015 paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine “Restrictions of Medicaid Reimbursement of Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the United States,” found that many state Medicaid programs were limiting access to HCV treatment DAAs. At the time, Taylor was an assistant professor of medicine at Brown University and director of the HIV/Viral Hepatitis Coinfection Program at The Miriam Hospital. One of her undergraduate students, Soumitri Barua, was the lead author for the paper.

Since the publication of the paper, some states have changed their Medicaid policies to allow for wider coverage of life-saving DAAs. The National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR) is tracking this progress and grades several states as failing. NVHR recommends that state Medicaid programs remove liver damage, sobriety and prescriber requirements, ensure hepatitis C coverage parity across Fee-For-Service and Managed Care Organization programs, and ensure transparency regarding hepatitis C coverage guidelines.

Taylor fears that DAA restrictions in Rhode Island and elsewhere are contributing to high incidence and reinfection rates at a time when elimination via expanded access to DAAs should be the goal for the biggest infectious disease killer in the U.S.

Being cured of HCV with DAAs brings tremendous emotional, physical, and psychological changes for patients that have been carrying this burden.

“We are seeing transformations in people who thought that they would die from HCV,” says Taylor. “With SVR, our patients are motivated to quit smoking and work on alcohol cessation. Relationships are being repaired as feelings of shame and stigma are alleviated. This is turning the field upside down—it used to be that it was acceptable for clinicians to consider their own perceptions of HCV treatment candidacy and readiness. Now national and international evidence-based guidelines support universal HCV treatment and prioritizing PWID. Well-designed studies will help us determine the benefits of letting PWID know that they are worthy of HCV treatment and cure.”

The World Health Organization has set a goal to eliminate viral hepatitis as a major public health threat by 2030. (Read the complete strategy in the WHO publication, Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016-2021: Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis.)

To achieve HCV elimination targets by 2030, higher proportions of PWID with HCV need to be diagnosed, treated and cured, states Taylor.

“The PWID who are most disenfranchised and isolated from society and healthcare must be engaged to reach this goal,” she explains. “Synergistic efforts must address HCV elimination and overdose prevention. Integrating HCV testing, diagnosis, treatment and prevention in a single setting is increasingly possible, through physical or virtual co-location. Amplifying the capacity for DAA prescribing by primary care providers, addiction medicine and infectious disease specialists should improve HCV treatment expansion,” adds Taylor. “Further research to evaluate care cascade interventions among PWID are needed as part of a systematic approach to reduce HCV-related morbidity and mortality and to eliminate HCV as a public health threat.”

“The PWID who are most disenfranchised and isolated from society and healthcare must be engaged to reach this goal,” she explains. “Synergistic efforts must address HCV elimination and overdose prevention. Integrating HCV testing, diagnosis, treatment and prevention in a single setting is increasingly possible, through physical or virtual co-location. Amplifying the capacity for DAA prescribing by primary care providers, addiction medicine and infectious disease specialists should improve HCV treatment expansion,” adds Taylor. “Further research to evaluate care cascade interventions among PWID are needed as part of a systematic approach to reduce HCV-related morbidity and mortality and to eliminate HCV as a public health threat.”

Lynn E. Taylor, MD is an HIV, viral hepatitis and primary care physician, clinical researcher, educator and public health advocate focused on care of hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) and HIV in vulnerable populations.

Lynn E. Taylor, MD is an HIV, viral hepatitis and primary care physician, clinical researcher, educator and public health advocate focused on care of hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) and HIV in vulnerable populations.

Dr. Taylor recently became a member of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health Resources and Services Administration's Advisory Committee on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and STD Prevention and Treatment. She served on the World Health Organization Guideline Development Group for Screening, Care and Treatment of Chronic HCV and as a member of the International Consensus Guidelines Committee Management of HCV in PWID for the International Network of Hepatitis in Substance Users.

For nearly two decades Dr. Taylor has worked to enhance HCV and HIV prevention and treatment for PWID, establishing free HIV/HCV testing, education, vaccination and referral sites, and developing on-site HCV care at methadone maintenance and HIV care programs. Dr. Taylor is Rhode Island site Principal Investigator for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute 5-year research award, “Clinical Management of HCV Infection: Patient-Centered Models of HCV Care for PWID.” She developed and directs Rhode Island Defeats Hep C (RID Hep C), a comprehensive program to Identify, Treat, Cure, Prevent and Eliminate HCV in Rhode Island.

Together with WaterFire, Dr. Taylor organizes one of the world’s largest HCV festivals, to raise awareness and diminish stigma – C is for Cure: A WaterFire Lighting for RI Defeats Hep C. The 2018 event will be held on July 28, in honor of World Hepatitis Day. Contact RID Hep C if you know a hep champion who should be honored that night as a Torch Bearer at the Olympic-style Opening Ceremony!

References and Related Links

Ly, K. N., Hughes, E. M., Jiles, R. B., & Holmberg, S. D. (2016). Rising mortality associated with hepatitis C virus in the United States, 2003–2013. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 62(10), 1287-1288.

A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C

C is for Cure WaterFire Lighting

HHS Viral Hepatitis website