"The first problem for all of us, men and women,

is not to learn, but to unlearn."

~ Gloria Steinem

Part one of this series on integrating behavioral health and primary care focused on getting yourself to the table—becoming a player in integration and systems redesign. This issue will look at what you do when you get there—the challenges and adaptations faced by behavioral health providers as they enter a more integrated care world.

You may not be accustomed to thinking of yourself as a behavioral health specialist, but in the integrated health care world, that is how you will likely be viewed. It's an important role and your colleagues from other disciplines will look to you for expertise in addiction and mental health treatment. It's a good idea to come up with your own response to the question "what is a behavioral health specialist and what can you do for primary care?" Ideas about this new role and presenting yourself were included in the previous issue in this series.

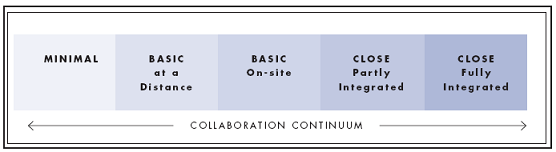

To some degree, the amount of adaptation you need to make will be proportional to the degree of integration in the program. Working in a fully integrated model will require significant adaptation as compared to part-time on-site work or an enhanced referral and partnership model. Many of the issues, however, remain the same: communicating, team models for treatment, wrap-around collaborative care, electronic health records, consumer's role, and issues related to meaningful use data and privacy. The diagram below, from the Milbank Foundation's Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care, shows varying degrees of integration (from minimal on the left to fully integrated on the right) and, defacto, the degree of adaptation which may be required by behavioral health specialists new to this model of service delivery (1):

Learning more about the various models will help you determine which will best suit your skills and preferences—the aforementioned Milbank Foundation report http://www.milbank.org/reports/10430EvolvingCare/EvolvingCare.pdf is a good place to start, as is SAMHSA-HRSA's website http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models. Think also about your current place of employment and what model is working or might make sense for your team.

The rest of this issue will primarily address the challenges of working in a fully integrated model, drawing heavily upon the experience and lessons learned from organizations that are successfully integrating behavioral health and primary care.

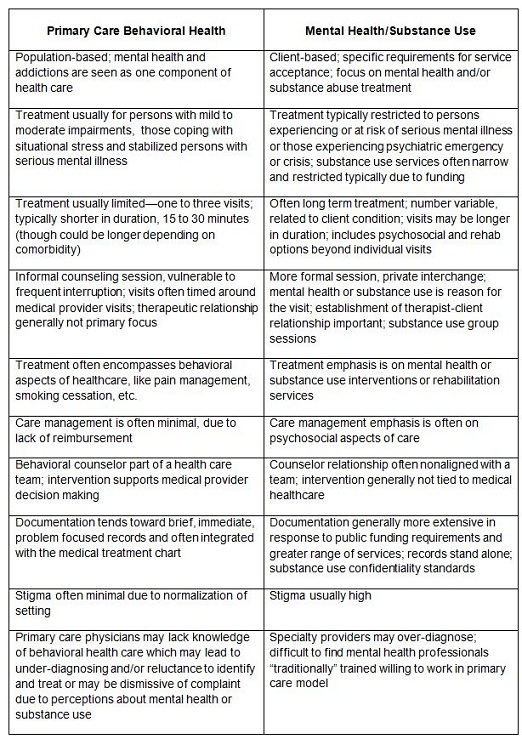

On of the best ways to see and feel the differences between your current work setting and what you may encounter in an integrated system is to visit and shadow one or more providers. The next best thing is to talk with people who have made this transition. Last, but also helpful, is to read as much as you can. Among other things, you'll find charts like the one below (2) which highlights some of the differences. A chart comparing traditional mental health and integrated care is available at http://www.ibhp.org/index.php?section=pages&cid=97 . Look at the differences and reflect on your own thoughts and feelings as you read them—those may be clues to your ability to adapt to this work.

Source:

http://primarycareforall.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Cultural-Differences.pdf

To the above we can add other challenges such as: language (are they clients, patients, customers?), attitudes about medication (doctors may be more pro-medication in general, though perhaps not as aware of its applicability to addiction treatment) and more.

Certain themes emerge when examining the personal qualities and characteristics needed to succeed in an integrated care setting. Clearly, someone moving into this type of service delivery needs to be willing to change and learn ("willing" is the minimum—being excited about is even better). The Milbank Report says: "The learning curve for existing behavioral health providers who wish to work in this fully integrated setting should not be underestimated. The new model of care will require a commitment to significant change. Change is built around developing the knowledge and skills to effectively implement validated screening tools, motivational interviewing, self-management, focused brief interventions/therapy, consultations, chronic disease models, clinical algorithms, disease management processes, medications, substance abuse screenings and interventions, recovery models, and cultural competencies. The therapist who has practiced in a highly structured fifty-minute appointment schedule will find a much faster paced environment in the primary care setting where practitioners work in fifteen-to-thirty-minute increments with frequent interruptions, consultations, and handoffs." (1)

As you reflect on integrative care and read the list of important qualities below, remaining open-minded and accepting is key. It's difficult to make changes in the pace, pattern and focus of our work. We often feel that our past approach is the only way, or the best way to offer services. The current climate and changing economics in the US will demand a shift in services and practice patterns. Working to address our own resistance is critical to moving forward with integrative care models.

Other important personal qualities include:

Flexibility—you will need to see more clients and spend less time with each of them. You may also need to adjust quickly to significant daily changes in pace, priority, work flow, and even in the physical workspace itself.

Belief in brief intervention—if you don't think that brief interventions are effective or if they are not your forte, a fully integrated team is probably not the setting for you. There will still be a need for more intensive, longer term counseling and therapy and if that suits your skills and style better, so be it.

Team orientation—you should enjoy being part of a treatment group and you must value and incorporate the perspectives of others. You may have to defer to others at times, and remember that everyone on the team will be learning new ways of functioning, not just you.

Good communicator—this comes up repeatedly and is multifaceted; even if you happen to be a person who communicates well in a variety of modes (oral, written, etc.), if you don't speak a common language with your partner providers, trouble ensues.

Holistic perspective—you must have a keen interest in looking at the whole person, including consideration of physical health issues which may even have to take precedence over behavioral health in some cases.

The National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare's webinar "Behavioral Health in a Primary Care Setting: Keys to Success" identified other important qualities of providers who successfully adapt to integrative care settings, including: those who are used to working in less structured settings (i.e. walk in or drop in settings, outreach work, etc.), have some medical training, have experience with or knowledge of medical diagnosis, and who have experience with and belief in shorter treatment models/modalities. They also identify two common practice characteristics with which one would need to become comfortable—"open access" and "warm handoffs". Open access is a patient-centered scheduling feature which is "used to facilitate hand offs and decrease down time". Open access is a source of resistance among most providers in the beginning, but the presenters also note that this structure "decreases no show rates" and "increases provider and patient satisfaction" (3).

Cherokee Health System has developed an effective integrated health care model, and their "Cherokee Academy's blog" (http://cherokeeacademy.wordpress.com/) points to the importance of the right "match" for those working in integrated settings: "Finding the right people to fill the roles… is vital. This is not a model for everyone. There is still a high demand for intensive counseling, traditional psychiatry and acute care; professionals who trained in those disciplines and who prefer that model of delivery will not function well in the key roles of an integrated care setting." (4).

So, if the qualities outlined above do not describe you, you may be better suited to being a referral partner rather than a member of the onsite integrated healthcare team—there is and will be a need for both.

What clinical skills do you need to become a valued and successful part of the integrated health care team? There are several lists circulating in the literature; Mauer et al. have identified the following as critical core competencies, which "can be any licensed practitioner--training, orientation and skills are the key:

If you compare your own skills and competencies to this list you may find areas in which you need additional training. In the future we will likely see more cross-training so different fields are better prepared to work together, but for now we are left to unlearn some things and re-educate ourselves on others. SAMHSA's network of Addiction Technology Transfer Centers (http://www.attcnetwork.org/index.asp) can be a useful resource for workforce development and training in these aspects of health care integration.

The skills list above also makes sense in light of the roles behavioral health consultants may be expected to fulfill in an integrated practice, including: "improving patient adherence, supporting patient self-management, supporting behavioral change, helping to decrease over or under utilization, helping clients reduce health-risk behaviors and increase health enhancing behaviors, monitoring and helping to improve population outcomes and providing consultation and training to the PC team". (5)

Another aspect of behavioral health care competency has to do with the special evidence-based practices used in integrated behavioral health/primary care settings. In some ways these approaches are more akin to an EAP-type counseling in their brevity and focus. Problem Solving Treatment-Primary Care (PST-PC), for example, teaches people how to solve the 'here-and-now' problems contributing to their depression and helps increase their self-efficacy. It typically involves 6-10 sessions, depending on the patient's needs (http://impact-uw.org/tools/pst_manual.html). Another approach is Solution Focussed Therapy (SFT) which "moves client focus off of what's wrong and onto what's right, stresses the resources and skills clients have, and helps them take the role of expert (which they hold anyway) and take responsibility from there for setting their own goals and reaching them. It's not about what's missing and causes woe, but what's present and can lead to happiness (http://www.psychpage.com/family/library/sft.htm). And, of course, Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy are also used extensively. On the primary care side, Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment, SBIRT, is an evidence-based practice which may be used and the referral can be made either to the behavioral specialist on staff, or to an outside provider if appropriate.

Cherokee Academy's blog provides some fitting advice relevant to behavioral health care integration: "Be Impeccable with Your Word, Don't Take Anything Personally, Don't Make Assumptions, and Always Do Your Best. It's a pretty simple blueprint for a successful start of a partnership. So much of the success of the project is based squarely on the foundation of the relationship between the people involved, and in turn the organizational relationship they create and nurture. Understanding each others missions, values, cultures, environments (business, funding, political, board, community) and languages is vital. Likely you share many of the same patients or demographics, but your approach to serving them is often very different. Understanding those differences and finding areas of common ground, mutual benefit and synergies is very important. If you don't take the time to appreciate these components before delving headlong into this complicated, sometimes thorny path of integrated care, those differences will make themselves known quickly in disguise of obstacles and barriers. If you take the time to build the relationship, align your values and missions, seek to learn about each other's worlds – there will be a time when you look back at those early days and recall fondly the courtship, discovery and relationship creation". (4)

If you like a change, a very fast-paced environment, teamwork, brief interventions, holistic approaches, and being on the cutting edge, the fully integrated primary care organization could be a dream come true for you. If you don't, one of the less integrated models may be a better match. In any case, the demand for behavioral health specialists will continue to grow, so finding the care model (wherever it falls on the integration continuum) that best matches your skills and personal goals is key to your work satisfaction and success with your clients and teams.

Series Author: Wendy Hausotter, MPH

Series Editor: Traci Rieckmann, PhD, NFATTC Principal Investigator, is editing this series.

The Addiction Messenger's monthly article is a publication from Northwest Frontier ATTC that communicates tips and information on best practices in a brief format.

Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center

3181 Sam Jackson Park Rd. CB669

Portland, OR 97239

Phone: (503) 494-9611

FAX: (503) 494-0183

A project of OHSU Department of Public Health & Preventive Medicine.