Being a strong link in the chain of support for patients using Medication-Assisted Treatment can make a huge difference in their recovery. Forging the cross-discipline relationships that provide a supportive net for those using MAT can also strengthen a substance abuse agency's position in the ongoing march toward healthcare integration.

Thus far, the Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) series of the Addiction Messenger has defined MAT, considered its place in the context of treatment and recovery, and discussed strategies for supporting patients using MAT in substance abuse treatment settings.

Part 3 will broaden the scope to discuss challenges and strategies related to MAT implementation, including finding and communicating with physicians, getting medications paid for, first steps in implementation, and effective outreach and services with special populations.

The final article of this three-part series will continue to draw from and highlight the new ATTC on-line training about MAT (1).

Utilization of MAT differs across treatment settings and geographic regions. Knowing where medications for addiction are provided, and by whom, is a critical piece of increasing access, and developing and maintaining relationships with physicians and other prescribers. Finding providers, however, can require strategic action, particularly in rural areas.

Opioid Treatment Providers

Some of the major dispensers of MAT are Opioid Treatment Providers (OTP). As discussed in Part 1, methadone prescribed for opioid addiction treatment must be dispensed by an "OTP" that is certified by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). OTPs have historically delivered methadone, but also increasingly deliver buprenorphine, and also naltrexone, including extended-release injectable naltrexone (Vivitrol), approved in 2010 for treating opioid addiction (4).

The good news is that the number of SAMHSA-certified OTPs, along with the patients they serve, is consistently on the rise. In 1993, for example, approximately 750 registered OTPs were treating about 115,000 patients in 40 States, along with the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands; and by 2005 the numbers of OTPs increased to about 1,100 sites, serving an additional four states and about 200,000 patients total (2). Even more recently – as of August 3, 2011 – there were 1,247 OTPs registered, and the only states without a single OTP were Wyoming, South Dakota, and North Dakota

(1: Module 1, Slide 18).

http://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx

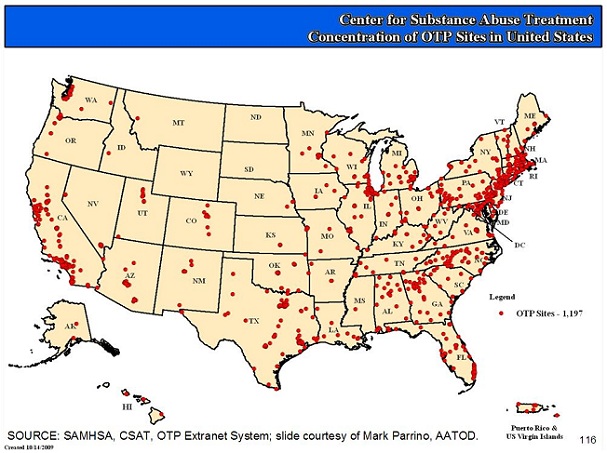

As the graph above indicates, OTPs are fairly well distributed on the east and west coasts and within large U.S. urban centers. Unfortunately, the SAMHSA tracking system also reveals that rural access to OTPs remains minimal, and relatively absent in rural southern and mid-western U.S.

It has been well documented in the literature that geographical access is an important determinant of treatment utilization in the general population. Among substance abusers, longer travel distances are associated with shorter length of stay and lower probability of treatment completion and utilization of aftercare services; also, ongoing utilization of and engagement in services (i.e. treatment retention) is especially important among patients using methadone because of the need for continued medication adherence required to achieve and sustain treatment gains (3).

In 2011, Rosenblum and colleagues published the results of a study that examined commuting patterns (including distance traveled and cross-state commuting) among 23,141 methadone patients enrolling in 84 OTPs in the U.S. (3) The study found that while the majority of OTP patients needed to travel a short distance to access medication-assisted treatment, six percent (about 1,400 patients) had to travel between 50-200 miles, and an additional eight percent (about 1,850) had to cross a state border to access MAT. The factors that were associated with a greater distance traveled included residing in rural areas in the Southeast or Midwest, younger age, non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity, and abuse of prescription opioids (as opposed to heroin).

As the study above shows, a significant number of OTP patients travel considerable distances to access treatment. To reduce obstacles to OTP access, policy makers and treatment providers should be alert to patients’ commuting patterns and to factors associated with them. Also, although many OTPs provide intensive supervision and support – e.g., specific medication schedules, psychosocial treatment, and other supportive services – providers should be on the look-out for strategies to increase patient-centered collaborative care models.

Also, importantly, given the limited access to OTPs in some geographic areas, private physicians are essential to increasing access to medications including those for opioid addiction, i.e. buprenorphine (Subutex®), buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone®), and naltrexone (ReVia®, Vivitrol®, Depade®); as well as those available for alcohol addiction, including naltrexone (ReVia®, Vivitrol®, Depade®), Disulfiram (Antabuse®), and Acamprosate Calcium (Campral®)

MAT for Opioid Addiction

A key resource for finding physicians who are able to prescribe buprenorphine in your local area is the Buprenorphine Physician and Treatment Program Locator: http://buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/bwns_locator/. SAMHSA maintains the on-line Locator to assist states, medical and addiction treatment communities, potential patients, and/or their families in finding information about the location of both physicians and treatment programs authorized to treat opioid addiction with buprenorphine.

The Locator – which includes a FAQ about MAT and other general information – lists physicians authorized to prescribe Subutex and Suboxone. It also lists treatment programs authorized to dispense (but not prescribe) Subutex, Suboxone, and also methadone. Note that the OTP Extranet System (described above) and the Buprenorphine Registry are two different registry systems, though both are maintained by SAMHSA. The OTP Extranet System tracks the number of Opioid Treatment Programs in each state, while the Buprenorphine Registry tracks physicians, and also treatment programs authorized under 21 U.S.C. Section 823 (g)(1) to dispense (but not prescribe) opioid treatment medications.

As of August 3, 2011, there were 12,874 physicians and 1,839 opioid treatment programs listed in the SAMHSA buprenorphine registry. All 50 states have at least a small handful of prescribing physicians and at least one OTP offering buprenorphine (1: Module 2; Slide 117). Supporting this trend, there is a steady rise in the distribution of buprenorphine, not only to opioid treatment programs, but – on an even more impressive scale – to pharmacies.

The Drug Enforcement Administration ARCOS (Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System) system tracks retail distribution of buprenorphine to pharmacies. According to ARCOS, since 2003 (the first full year following FDA approval of Subutex and Suboxone), sale of these medications has increased consistently in the U.S., from less than five million grams distributed to pharmacies in 2003 to more than 50 million grams distributed in 2007 (the latest year for which ARCOS data was available).

Another resource for locating treatment providers – in general, but also searchable by those whose services include methadone and/or buprenorphine – is SAMHSA's Resource Treatment Locator:

http://dpt.samhsa.gov/treatment/treatmentindex.aspx.

Physicians who prescribe buprenorphine aren't required to register in the Buprenorphine Physician and Treatment Program Locator. There are several strategies, though, that can be employed to locate these non-listed providers, and also prescribers of other types of MAT, including other medications for opioid treatment.

Notably – related to increased opportunities for linking with providers of MAT for opioid addiction – while buprenorphine must be prescribed by a physician who has met specific educational requirements and obtained a waiver from the US Drug Enforcement Agency, naltrexone (ReVia®, Vivitrol®, Depade®) can be prescribed for opioid dependency by any healthcare provider who is licensed to prescribe medications, i.e., without special training or waiver.

The following list of strategies for locating physicians who prescribe all types of MAT is summarized in an introductory publication about MAT and implementation entitled NIATx: Getting Started with Medication-Assisted Treatment with Lessons from Advancing Recovery (5). The authors suggest several sources for increasing access to prescribing physicians for patients with substance use disorders. Counselors, providers, and family members might want to reach out to:

If a provider still can't be located using these strategies, it might be possible to successfully advocate to local physicians and/or clinics and request that they expand services to include MAT. Training is one mechanism to begin these conversations and increase interest. The Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network – in the context of healthcare reform and increasing integration of services – has been expanding its audience to include more training for mental health and primary care professionals. Also, as mentioned in part 1, the new ATTC MAT on-line training includes a separate track of modules for primary care providers, in addition to its track for behavioral health (1).

Another challenge is developing skills to improve collaboration with physicians. The following is a list of tips behavioral health professionals can utilize in communicating with primary care providers (1: Module 2, Slides 108-113). Before reports or other materials can be shared, of course, patient consent and a signed release of information must be obtained.

TIP 1: Send a written report

The goal of communicating via written report is to increase the likelihood that concerns and information will be included in a patient's medical record. Information in clinical records is more likely to be acted on than records of phone calls and letters.

TIP 2: Make it look like a report – and be brief

The second tip is to make the information you wish to relay to the physician look like a report – and to keep it brief. Be sure to include a date, the client's name, and their social security number; also, keep in mind that medical-consultation reports are optimally one page or less, since longer reports are less likely to be read.

TIP 3: Include prominently labeled sections

Next, when you draft the report to send to the physician, be sure to include sections that are prominently labeled. The following are suggested headings: "Presenting Problem", "Assessment", "Treatment and Progress", and "Recommendations and Questions".

TIP 4: Keep the tone neutral when providing details

Finally, provide details about the client's use or abuse of prescription medications. Avoid making direct recommendations (since it may be outside your scope of practice to do so); instead, allow physicians to draw their own conclusions based on the information provided. This will enhance alliances with physicians, and makes it more likely they will act on the input.

Communicating with Physicians – Sample Form

A sample Treatment Coordination Report, developed by Mid-America ATTC, is available for free download, at: http://www.attcnetwork.org/regcenters/productdetails.asp?prodID=447&rcID=5.

Professional duty dictates that a report should be updated whenever a client's condition or situation changes in a manner thought to affect the client's general health and/or medical care. Continue attempts to coordinate care when it is in a patient's best interest, even if their physician appears not to respond. Similarly, and in reminder, a release of information must always be present and current in the file, if sharing across settings and agencies.

This series has already discussed some of the main broader challenges in supporting patients on MAT, i.e., the stigma associated with MAT, discrimination, and locating and collaborating with providers of MAT.

As mentioned in Part 2 of this series, in 2011 the ATTC Network conducted a series of focus groups about MAT throughout the U.S., in prelude to creating a new MAT curriculum (1). A barrier consistently identified in focus groups was the disconnect between financial policies and clinical recommendations, i.e., that publicly-available funding and insurance coverage often limit on-going access to MAT. An example may be providing 90 days of buprenorphine, when the doctor and individual identify a longer period of need, a factor that often compromises success (1: Module 3, Slide 57). The following list of ideas may help providers bridge this gap (5):

Paying for MAT: Lessons Learned from MAT Implementation

In many settings, individuals will have insurance that may cover addiction medication. Contacting the insurance company will help determine coverage. Parity regulations may also continue to expand insurance availability and coverage.

Medicaid formularies vary by state. A good resource for understanding state and local rules is the state methadone authority.

States have discretion with block grant funds. Many MAT providers, through demonstrating their success, have helped get funds established specific to MAT.

In addition, providers and families have been able to work with FQHCs to help access medications for patients with substance use disorders:

Many medications can be cost prohibitive, but families and individuals may find the resources for private pay, especially when viewed in comparison with the cost of continued drug use.

A variety of barriers have prevented the widespread use of MAT. These include a lack of financing for medication, insufficient organizational infrastructure to deliver medication, state and county funding and regulatory obstacles, physician training and certification, staff and client resistance, and community attitudes (5). In this scenario, where does an organization start?

An interesting and useful publication – NIATx: Getting Started with Medication-Assisted Treatment with Lessons from Advancing Recovery (5) – includes many lessons related to these barriers that emerged from the efforts of several organizations to establish MAT programs in their organizations in partnership with SSA offices. The organizations were grantees in a national five-year initiative (2005-2010) entitled Advancing Recovery: State/Provider Partnerships for Quality Addiction Care (AR), which was funded by Robert Wood Johnson and co-directed by the Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx) and the Treatment Research Institute (TRI).

In the NIATx publication (5: pg. 5), Clark and colleagues identify education as a key first-step for implementation: "Educating staff on the benefits of MAT may need to be an initial focus for many organizations. Some of the most experienced addiction professionals were trained in the abstinence-based era. Helping staff understand how their clients will benefit from MAT is a critical part of securing their buy-in." In other words, treatment "ideology" can pose a significant challenge – i.e., 12-step model treatment programs are less likely to adopt MAT medications, and place a greater emphasis on "abstinence", viewing MAT as substitution, replacing one drug with another (6).

One treatment agency involved in the AR Initiative, the Addiction Resource Center (ARC) in Brunswick, Maine, began to survey staff annually to quantify the need for ongoing MAT training, using questions such as the following (5: pg. 7):

Many of the objections to MAT are based on old training or misinformation, although others may be well founded and familiar to treatment staff. MAT is complex and the need to listen to all viewpoints is critical. Staff members, while well intentioned, may need to be educated on the benefits and limitations of MAT. Also, senior clinical staff members are often in a position to train new staff and guide treatment decisions, and it is imperative that staff members receive the education and knowledge they may need regarding MAT.

The end results were well worth it, as Advancing Recovery West Virginia, another project that participated in the AR initiative, explains (5: pg. 10):

"Over the course of our project, the skeptics changed their minds when

they began to see how medication-assisted treatment, combined with

counseling and supportive services, worked for people they had not

been able to help in the past. More than one clinician has described the results produced by this approach as 'miraculous'."

As this underscores, the most powerful advocate of all for MAT is the power of recovery.

Reaching out to and serving people of differing ethnicities and cultures, to ensure they have equal access to MAT, brings its own complex challenges and rewards. While having an open mind and heart is a great beginning, knowledge of cultural groups being served is key to providing appropriate (and respectful) service. Specific tools and resources for reaching and serving special populations with MAT, however, aren't readily available, which was part of the impetus behind regional ATTCs collaboratively creating new outreach tools and training.

The new ATTC MAT on-line training includes four modules focusing on specific population groups (i.e., African Americans, Asian and Pacific Islanders. Hispanic and Latino communities, and Native American/Alaska Native cultures). Each module covers information in several key topic areas, e.g., demographics, language, levels of education, levels of acculturation/enculturation, cultural histories, substance use patterns and preferences, health insurance/financial/bureaucratic barriers, and – importantly – traditional health beliefs and available research. Drawing on this information, the modules also offer strategies and implications for treatment, including outreach and engagement.

If you would like to download or view the culturally-tailored outreach materials, or curricula, please visit:

http://www.attcnetwork.org/explore/priorityareas/wfd/mat/index.asp

Medications to support recovery will continue to offer promise and hope for many individuals and their families. It is the goal of the MAT series, and the creators of the ATTC on-line curriculum, that all practitioners become familiar with the benefits, limitations, and applications of MAT.

For more information, please consider exploring the resources listed below and in earlier articles of this series, or contact your regional ATTC for information, training, and/or more ongoing assistance with implementation: www.attcnetwork.org.

Author's Acknowledgement and Note: The author acknowledges and thanks the individuals and organizations involved in the collaborative process that created the ATTC MAT curriculum (1), the main source for this series. This includes the funder (SAMHSA-CSAT), focus group participants, and the curricula authors. Also, while the author originally intended to include more about serving special populations in this series, it was decided the topic warrants its own Addiction Messenger series.

Series Author: Lynn McIntosh is a Technology Transfer Specialist for the Northwest Frontier ATTC and the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Series Editor: Traci Rieckmann, PhD, NFATTC Principal Investigator, is editing this series.

The Addiction Messenger's monthly article is a publication from Northwest Frontier ATTC that communicates tips and information on best practices in a brief format.

Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center

3181 Sam Jackson Park Rd. CB669

Portland, OR 97239

Phone: (503) 494-9611

FAX: (503) 494-0183

A project of OHSU Department of Public Health & Preventive Medicine.