Erin L. Winstanley, Ph.D.

March 2019

All too frequently we read reports in the media of communities that are considering limiting overdose survivors' access to naloxone, a life-saving medication that reverses respiratory depression caused by an opioid overdose. For those working in the addiction treatment system, we know that relapse is part of the recovery process for many clients with an opioid use disorder (OUD). We cannot predict the number of relapses a client may experience on their path to recovery, but research suggests that it may take cigarette smokers 30 or more quit attempts to achieve long-term cessation (Chaiton et al. 2016). Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) services are critical to ensuring that clients with an OUD have another chance to achieve recovery.

There were 192 overdose deaths every day in 2017 in the United States (U.S.) and approximately 67.8% of these deaths involved opioids (Scholl et al. 2018). The total number of overdose deaths has increased every year since 2008 (Rudd et al. 2016), when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) first recognized drug overdose as an epidemic. The epidemic of overdose death has evolved over time, emerging in three distinct waves. Beginning in 1999, most of the deaths involved prescription opioids, which switched to heroin in 2010 and then to synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) in 2013. Overdose deaths only represent the tip of the iceberg, as for every fatal heroin overdose there are an estimated 20-30 non-fatal overdoses (Darke et al. 2003).Combined fatal and non-fatal overdoses place a significant burden on our health care system, and the annual estimated cost of the opioid epidemic in 2013 was $78.5 billion (Florence et al. 2016).

The Oxford English dictionary defines overdose as “an excessive and dangerous dose of a drug.” The hallmark symptom of an opioid overdose is respiratory depression, defined as 12 breaths per minute or less (Boyer 2012). An opioid overdose does not occur only when someone takes too much; it can also occur when opioids are used in combination with other central nervous system depressants such as alcohol and benzodiazepines. An individual’s risk of an opioid overdose may be elevated if they have an underlying medical condition that causes decreased respiration. Some national experts are advocating for the use of ‘drug intoxication’ instead of ‘overdose’ because it is a more accurate term. Research has found that individuals misusing prescription opioids perceive overdose as occurring when you take “too much” of a drug – hence, they do not perceive themselves as at-risk (Daniulaityte et al. 2012). Overdose prevention education is used to ensure that at-risk individuals and bystanders can recognize the symptoms, as well as understand the contributing causes.

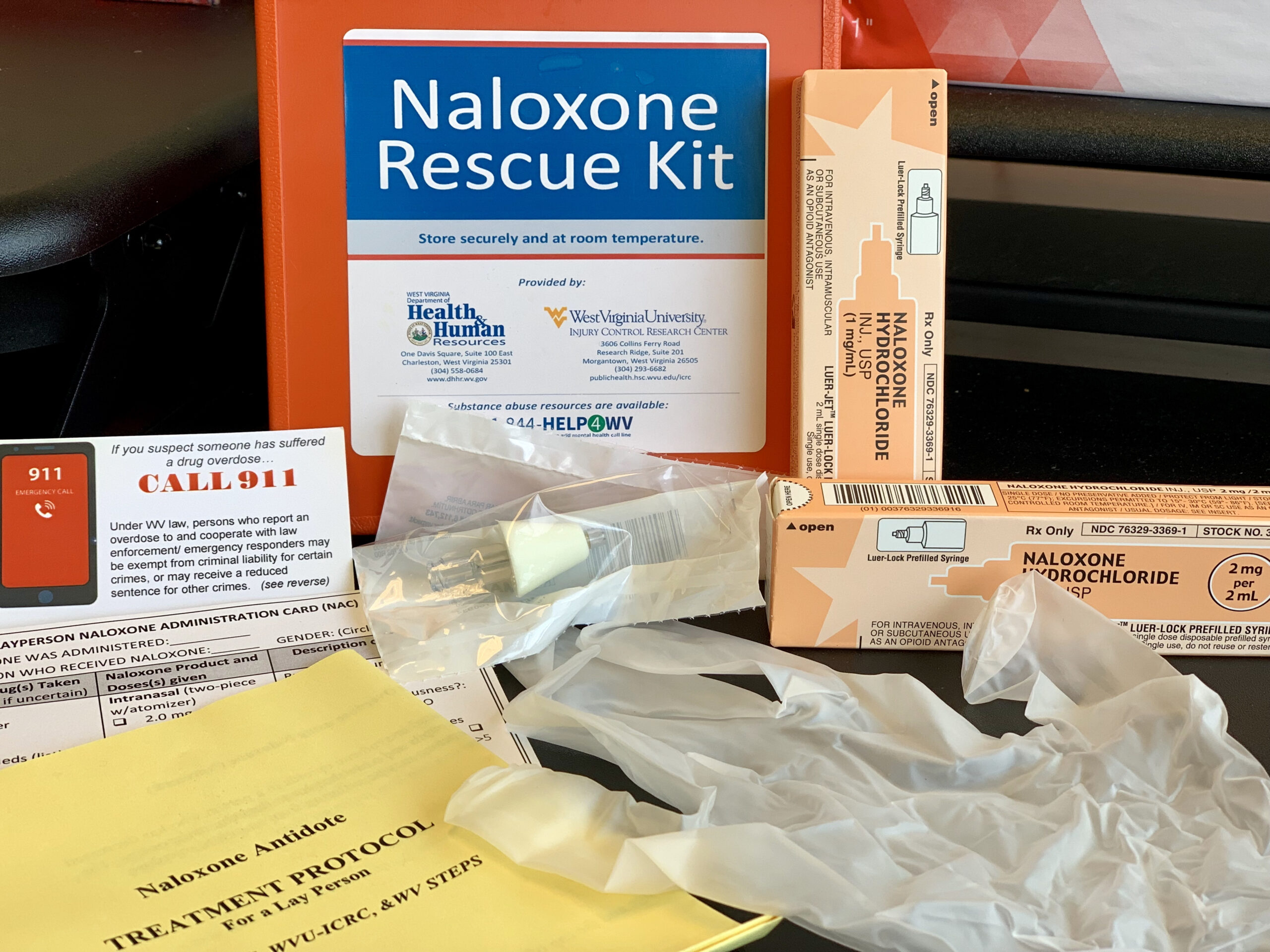

Naloxone is a fast-acting mu opioid antagonist, with no potential for abuse, that has routinely been used in medical settings since the 1970s (Boyer 2012). Naloxone is a very safe medication; side effects rarely occur. It has a very specific mechanism of action, so that if it were accidentally administered to someone that was not experiencing an opioid overdose, then it would have no effect. Naloxone requires a prescription, and it is available in injectable, intranasal or auto-injector formulations. Naloxone has a short half-life and may need to be re-administered if long-acting opioids, like methadone, were used. It is advisable to consider 1) the patient population, 2) product cost, and 3) the availability of highly potent synthetic opioids, such as illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF), when determining which formulation to use. More about the different formulations, billing options, and dispensing instructions is available at PrescribetoPrevent. Anecdotal reports suggest that naloxone may increase risk behaviors, that individuals may use greater amounts of opioids knowing that they may be ‘saved.’ However, there is no empirical evidence to support these reports (Kerensky & Walley 2017). Further, naloxone precipitates withdrawal, and it essentially extinguishes the “high.” Once naloxone is administered, the party is over.

OEND programs deliver services to individuals at-risk of experiencing an opioid overdose and bystanders that may witness an overdose. They provide education on how to appropriately identify and respond to an overdose, as well as train participants on how to use naloxone to reverse an overdose. OEND programs are effective at increasing participants’ knowledge of overdose risk factors (Clark et al. 2014; Wheeler et al. 2014),and community distribution of naloxone has been found to be highly cost- effective (Coffin & Sullivan 2013).

The Chicago Recovery Alliance (CRA) is recognized as the first OEND in the U.S. that started overdose prevention services in 1996. Dan Bigg is one of CRA’s founders; he is known for promoting harm reduction and #anypositivechange. Dan challenged us to step outside of the dichotomy of illicit drug use versus complete abstinence to recognize both the reality and importance of self-defined positive change. OENDs historically have been located within harm reduction programs and are increasingly being developed in other community-based and health care settings. Injectable formulations of naloxone are preferable in harm reduction settings as injection drug users are knowledgeable about the administration route, and it is significantly cheaper. Further, naloxone has poor nasal bioavailability, and injectable formulations may be more effective at reversing overdoses that result from highly potent synthetic opioids (Winstanley 2016). For OUD clients in recovery, an injectable formulation may be a relapse trigger, and these clients may be reluctant to obtain naloxone at harm reduction programs that primarily serve illicit drug users.

Few OEND programs have been tailored specifically for clients in OUD treatment or recovery, despite the significant risk of overdose if someone relapses to opioid use after a period of abstinence. Based on my experience with OEND services in a residential addiction treatment program, there are several considerations in tailoring programming for OUD treatment settings.

Few OEND programs have been tailored specifically for clients in OUD treatment or recovery, despite the significant risk of overdose if someone relapses to opioid use after a period of abstinence. Based on my experience with OEND services in a residential addiction treatment program, there are several considerations in tailoring programming for OUD treatment settings.

In the initial implementation phase of our OEND program, we encountered client resistance that we did not anticipate. Some clients perceived naloxone distribution as the program staff not believing in their ability to remain abstinent after treatment.

We suspected that other clients were resistant because of the self-stigma associated with OUD; perhaps some clients did not believe that their own lives were worth saving, and, in fact, some media reports expressed similar sentiments by suggesting limits on naloxone administrations. The introduction to the overdose education was carefully reframed to state that hopefully clients would never need the naloxone for themselves and they could use it to save someone else’s life. In fact, one of the first OEND participants used naloxone to save her mother just shortly after she was discharged from treatment.

OUD clients receiving methadone or buprenorphine have the greatest risk of overdose during the first month of treatment and if they discontinue treatment early (Cornish et al. 2010). This is due to the high risk of relapse early in treatment or after discontinuing medication-assisted treatment (MAT). If the client’s family and friends are not aware of the relapse, perhaps due to stigma and shame, they may not recognize non-responsiveness or unconsciousness as an overdose. Priority populations in OUD treatment for naloxone distribution would include:

1) individuals waitlisted for treatment,

2) clients that leave inpatient care against medical advice or drop out of MAT treatment, and

3) clients who report having previously experienced a non-fatal overdose. Priority clients, whenever feasible, should be directly given naloxone rather than a prescription.

OUD clients with co-occurring mental health disorders are also a priority population that may need enhanced services. Nationally, it is estimated that 8-13% of overdose deaths are intentional (suicide) (Hedegaard et al. 2018), and given the challenges in classifying overdose intentionality, many assume that the proportion of intentional overdoses is significantly higher. Substance use disorders commonly co-occur with other psychiatric disorders, and overdose is a common method of suicide; clients frequently report depressive symptoms in the early phases of treatment. OUD clients may have witnessed friends or family members die of an overdose that results in feelings of grief, as well as secondary trauma. OEND services in the context of OUD treatment should be aware of the overlapping risk of suicide and overdose, as well as consider screening clients to ensure the provision of appropriate mental health services.

The CDC’s Evidence-based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose recommends universal naloxone distribution to clients receiving OUD treatment; further, the Federal Guidelines for Opioid Treatment recognize OEND as an essential service for clients and their family members. State health departments may be able to provide local data on overdose rates, overdose prevention programs, and other resources. For example, the Ohio Department of Health sponsors a community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution program that includes an implementation tool kit. The FDA is working to facilitate the regulatory requirements for naloxone to become available without a prescription. In the meantime, most states have passed legislation that allows pharmacies to dispense naloxone without a prescription for a specific person through standing orders and other mechanisms. States have also passed legislation that protects naloxone prescribers and bystanders that administer naloxone from liability. Information on state-specific legislation related to OEND is available here. While naloxone has become significantly easier to obtain over the past few years, it can still be complicated as not all pharmacies fill naloxone prescriptions or are able to bill insurance for bystanders with naloxone prescriptions.

The CDC’s Evidence-based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose recommends universal naloxone distribution to clients receiving OUD treatment; further, the Federal Guidelines for Opioid Treatment recognize OEND as an essential service for clients and their family members. State health departments may be able to provide local data on overdose rates, overdose prevention programs, and other resources. For example, the Ohio Department of Health sponsors a community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution program that includes an implementation tool kit. The FDA is working to facilitate the regulatory requirements for naloxone to become available without a prescription. In the meantime, most states have passed legislation that allows pharmacies to dispense naloxone without a prescription for a specific person through standing orders and other mechanisms. States have also passed legislation that protects naloxone prescribers and bystanders that administer naloxone from liability. Information on state-specific legislation related to OEND is available here. While naloxone has become significantly easier to obtain over the past few years, it can still be complicated as not all pharmacies fill naloxone prescriptions or are able to bill insurance for bystanders with naloxone prescriptions.

The SAMHSA Overdose Toolkit and PrescribetoPrevent have excellent resources for organizations that want to integrate OEND services. A systematic review of OEND programs found that overdose prevention education can be delivered in 10 to 60 minutes in various formats including in-person delivery to individuals or groups, as well as by playing a video recording of the training. An estimated 44% of OUD clients receiving MAT have experienced a non-fatal overdose, and 87% have witnessed an overdose (Katzman et al. 2018); they may have experience using non-recommended strategies in response to an opioid overdose. Group-based education, if feasible, may provide the opportunity to discuss why some strategies may not work and encourage participants to explore other treatment approaches.

The SAMHSA Overdose Toolkit and PrescribetoPrevent have excellent resources for organizations that want to integrate OEND services. A systematic review of OEND programs found that overdose prevention education can be delivered in 10 to 60 minutes in various formats including in-person delivery to individuals or groups, as well as by playing a video recording of the training. An estimated 44% of OUD clients receiving MAT have experienced a non-fatal overdose, and 87% have witnessed an overdose (Katzman et al. 2018); they may have experience using non-recommended strategies in response to an opioid overdose. Group-based education, if feasible, may provide the opportunity to discuss why some strategies may not work and encourage participants to explore other treatment approaches.

We cannot and should not give up helping clients have another chance at recovery; relapse does not need to be a death sentence – instead, it can be an opportunity to re-engage individuals in treatment. Unfortunately, not everyone is willing or able to achieve recovery. As communities are increasingly overwhelmed by the social and economic costs of the opioid epidemic, it’s important to not succumb to compassion fatigue or to give up hope.

Even if it takes a client 30 relapses to achieve long-term recovery and naloxone ($135 per kit) is used to reverse 30 opioid overdoses – the total cost to save their life is a mere $4,050; which is less than the average cost of 3 days in hospital. OUD treatment programs can integrate OEND services that will undoubtedly save their clients lives.

References

Armenian, P., Vo, K. T., Barr-Walker, J., & Lynch, K. L. (2018). Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: a comprehensive review. Neuropharmacology, 134, 121-132.

Boyer, E. W. (2012). Management of opioid analgesic overdose. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(2), 146-155.

Chaiton, M., Diemert, L., Cohen, J. E., Bondy, S. J., Selby, P., Philipneri, A., & Schwartz, R. (2016). Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ open, 6(6), e011045.

Clark, A. K., Wilder, C. M., & Winstanley, E. L. (2014). A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. Journal of addiction medicine, 8(3), 153-163.

Coffin, P. O., & Sullivan, S. D. (2013). Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Annals of internal medicine, 158(1), 1-9.

Cornish, R., Macleod, J., Strang, J., Vickerman, P., & Hickman, M. (2010). Risk of death during and after opiate substitution treatment in primary care: prospective observational study in UK General Practice Research Database. Bmj, 341, c5475. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5475.

Daniulaityte, R., Falck, R., & Carlson, R. G. (2012). “I’m not afraid of those ones just ‘cause they’ve been prescribed”: Perceptions of risk among illicit users of pharmaceutical opioids. International journal of drug policy, 23(5), 374-384.

Darke, S., Mattick, R. P., & Degenhardt, L. (2003). The ratio of non‐fatal to fatal heroin overdose. Addiction, 98(8), 1169-1171.

Florence, C., Luo, F., Xu, L., & Zhou, C. (2016). The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical care, 54(10), 901.

Hedegaard, H., Bastian, B.A., Trinidad, J.P., Spencer, M., Warner, M. (2018). Drug most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011-2016. National vital statistics reports, 67(9):1-14.

Katzman, J.G., Takeda, M.Y., Bhatt, S.R., Balasch, M.M., Greenberg, N., Yonas, H. (2018). An innovative model for naloxone use within an OTP setting: A prospective cohort study. Journal of addiction medicine, 12:113-118.

Kerenskey, T., Walley, A.Y. (2017). Opioid overdose prevention and naloxone rescue kits: What we know and what we don’t know. Addiction science & clinical practice, 12:4 DOI 10.1186/s13722-016-0068-3.

Paulozzi, L., Dellinger, A., Degutis, L. (2012). Lessons from the past. Injury prevention, 18:70.

Rudd, R. A. (2016). Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 65.

Wheeler, E., Davidson, P. J., Jones, T. S., & Irwin, K. S. (2012). Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 61(6), 101.

Winstanley, E. L. (2016). Tangled‐up and blue: releasing the regulatory chokehold on take‐home naloxone. Addiction, 111(4), 583-584.

Erin L. Winstanley, Ph.D.

Dr. Winstanley is an Associate Professor at West Virginia University, Department of Behavioral Medicine and Psychiatry. Dr. Winstanley received her doctoral degree from The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and she has over 18 years of experience as a behavioral health services researcher. Her current research is focused on reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with the opioid epidemic, as well as the use of technology to improve access and quality of behavioral health services. You can follow her on Twitter at @DrEWinstanley.