Jamey J. Lister, PhD, MSW, Assistant Professor, Wayne State University

March 11, 2022 Editor’s note: Jamey Lister, Ph.D, is now an Assistant Professor, Rutgers University School of Social Work.

Contact: [email protected]

Overview of the opioid epidemic and treatment barriers

A staggering number of people continue to die from overdose deaths. In 2017, nearly four times as many people died from drug overdoses than in 1999 (Hedegaard, Minino, & Warner, 2018). Even more frightening, the death-rate increase from 2014 to 2017 was steeper than any period of the opioid epidemic (Hedegaard et al., 2018). The states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania characterize this rapid increase with 114% and 102% three-year rises in overdose deaths respectively (CDC, 2019a). In 2017, the states of West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania lost the greatest rates of people, all more than double the national average (CDC, 2019a). Furthermore, nearly half of U.S. states experienced significant increases in overdose deaths between 2016 and 2017 (CDC, 2019b).

Despite this ongoing public health burden, very few people can readily access evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) (Jones, Campopiano, Baldwin, & McCance-Katz, 2015). A recent estimate in California (Clemans-Cope, Epstein, & Wissoker, 2018) highlights between 48 and 70 percent of people with OUD lack local access to buprenorphine or methadone treatment. Rural Americans are an especially hard-hit group for treatment shortages. In Michigan, 55 of 57 rural counties lack an opioid specialty clinic (Lister et al., 2019). While treatment is comparatively more available in urban areas, many residents experience barriers related to health insurance, poverty and financial challenges, and a lack of reliable transportation (Knopf, 2017; Lister, 2017). As an illustration, we found in a study of publicly insured African American patients, living more than five miles from the methadone clinic was a determinant of treatment dropout even after accounting for other factors (Lister, Greenwald, & Ledgerwood, 2017).

Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to these problems. One potentially underutilized avenue to promote change is the field of social work – the most common profession to interface with people dealing with addiction (Bowen & Quinn, 2015). Therefore, I describe a practical set of strategies geared toward social workers to help the profession comprehensively combat the opioid epidemic.

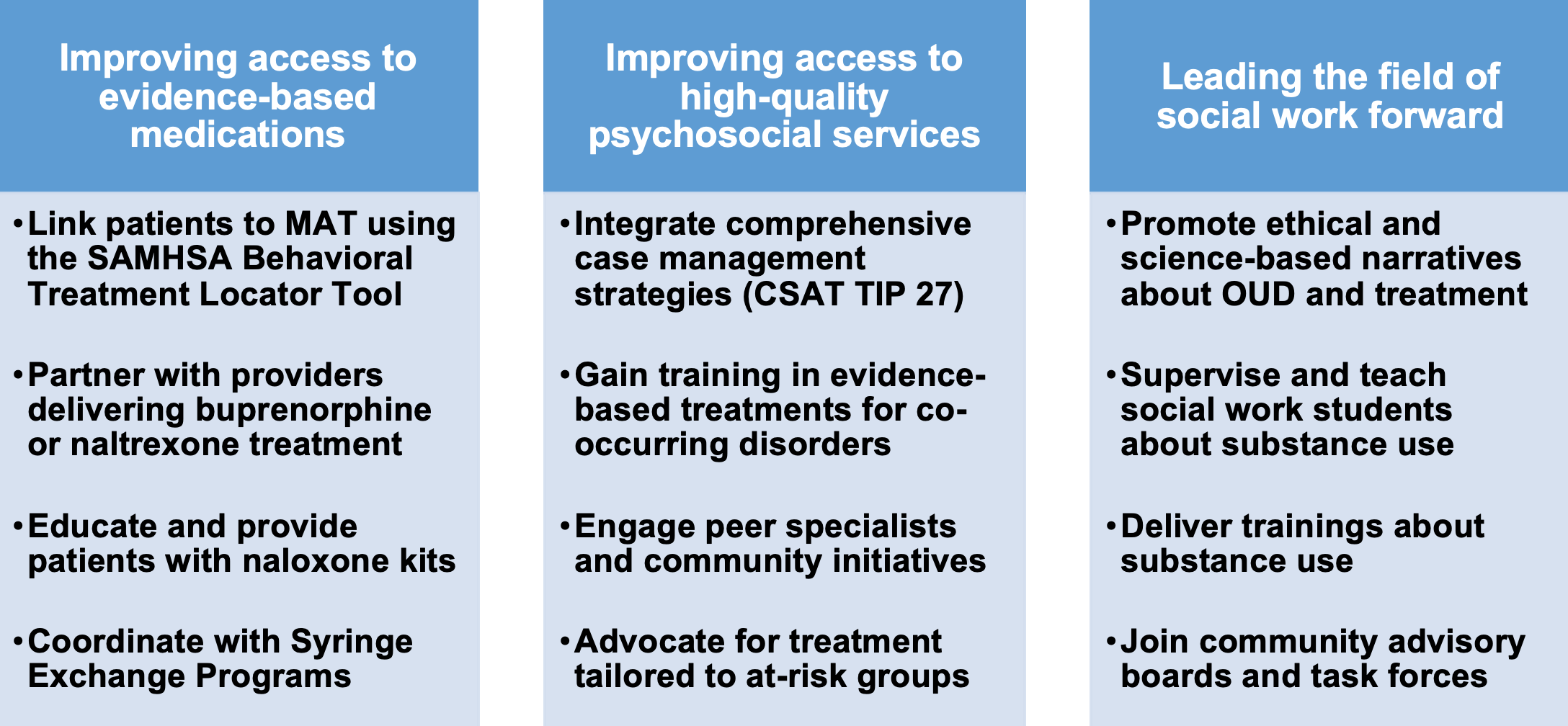

Solution #1: Improving access to evidence-based medications

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is the preferred OUD treatment among leading substance use organizations (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2015; World Health Organization, 2017). MAT includes medications like methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone combined with psychosocial services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018). Traditionally, OUD patients accessed MAT through methadone clinics (“opioid specialty clinics”), though it has become increasingly common to access buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone treatment in non-specialty settings (Dick et al., 2015) such as family medicine clinics.

One way social workers can help improve access to MAT is by using the SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Locator Tool. The Tool is free to the public and offers accurate information for opioid specialty clinics, which are accessible for many people living in urban areas. I recommend social workers seeking to facilitate linkages with buprenorphine treatment use both the Tool and word-of-mouth information from reliable sources, as some buprenorphine practitioners do not list themselves publicly, and others are not actively providing services.

Beyond helping to connect patients to local MAT options, social workers in non-specialty settings (e.g., community mental health, primary care) can advocate for practitioners to obtain buprenorphine waivers (SAMHSA, 2019). Due to the requirement for psychosocial treatment once a patient receives buprenorphine treatment, social workers delivering these supports can help increase the feasibility that practitioners in their setting take on patients (Andrilla, Coulthard, & Larson, 2017). By comparison, extended-release naltrexone, the third medication approved by the FDA for treating OUD (SAMHSA, 2016), can be prescribed by any healthcare professional licensed to prescribe medication. The medication requires patients to be detoxed from illicit opioids and opioid medications for 7-10 days, but the broader network of eligible providers offers the potential to expand access to MAT in a way not currently possible with methadone or buprenorphine.

Another way that social workers can intervene is by facilitating access to naloxone (Narcan®), a medication that can reverse the complications of an opioid overdose. Social workers can promote uptake by educating patients about naloxone, directly providing this medication to patients in the clinic, and gaining training in administering naloxone. They can also partner with community stakeholders (first responders, libraries, correctional settings, and homeless shelters) looking to administer and supply this medication. Last, social workers can help reduce the harms associated with injection drug use (i.e., infectious disease transmission) by building partnerships with local Syringe Exchange Programs.

Solution #2: Improving access to high-quality psychosocial services

While the medication component of MAT is imperative for OUD treatment (Amato et al., 2005; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, & Davoli, 2014), studies have shown patients receiving MAT have an even better chance at recovery when provided with concurrent psychosocial services (Salamina et al., 2010). Service delivery options that offer the most promise for patient outcomes include integrating comprehensive case management strategies from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (Treatment Improvement Protocol 27, 2000), and gaining training and specialization in delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for co-occurring mental health disorders like depression, anxiety, and PTSD (Barlow, 2014). These evidence-based approaches have the potential to improve patient outcomes more than generalist approaches or abstinence-based interventions that omit the medication treatment component.

Social workers can also connect with prevention and treatment options that typically occur in the community or non-specialty settings. Options such as peer recovery specialists and patient navigators offer a promising approach that can engage people with OUD in recovery efforts (Powell, Treitler, Peterson, Borys, & Hallcom, 2019). Building relationships with community-based initiatives like Families Against Narcotics and Hope Not Handcuffs has the potential to not only serve the person with OUD, but also improve matters for the family, community, and criminal justice system.

One other critical aspect that social workers bring to the table is their sensitivity to the differential needs of at-risk groups (Lister, Brown, Greenwald, & Ledgerwood, 2019). Social workers are encouraged to advocate for more research and treatment tailored to racial minorities, low-income populations, and approaches addressing gender-specific needs. The guideposts outlined in The Grand Challenges for Social Work (Uehara et al., 2014) offer a sound framework that social workers can use to anchor their service efforts and help communicate values with other professions. Two specific challenges “Achieving Equal Opportunity and Justice” and “Closing the Health Gap” are of particular relevance to the opioid epidemic.

Solution #3: Leading the field of social work forward

In my experience, social workers are compassionate people who, more than anything, wish to improve the quality of life among their patient population. As a field, we promote ethical practice by serving on behalf of marginalized groups, while also respecting the patient’s dignity and ability to self-determine. Beyond these values, we have a responsibility to promote and deliver evidence-based practices. With this in mind, it is essential for social workers to push back against unethical and pseudo-scientific perspectives on OUD and treatment. A few examples of these narratives include “medication-assisted treatment replaces one addiction for another”; “people with addiction cannot be trusted”; and, “people with addiction will never change.” Not only are these narratives in violation of the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics (2008), but they diverge from the scientific literature. Given our regular interaction with patients and practitioners, our ability to reframe these into productive narratives has the potential to decrease stigma and promote help-seeking for addiction.

There are also instrumental ways social workers can lead the field forward. Those with professional experience involving substance use can provide field supervision to social work students during placements in behavioral health settings. They can also teach substance use courses at local universities, lending real-world experience that research-oriented faculty often do not have. Another option is for social workers to deliver trainings related to psychosocial services specific to OUD populations for audiences of interdisciplinary health scientists, practitioners, and policymakers. Last, it is imperative that the voices of social workers are part of task forces and community advisory boards that help improve coordination, trust, and knowledge exchange between community members and professional stakeholders.

Conclusions

The opioid epidemic has hit all of our communities hard. The path to helping those in our communities achieve long-term recovery requires both new ideas and a long-term focus. The field of addiction has long called for greater involvement from social workers, and the opioid epidemic is something that has unified us all, social workers included, through the loss of loved ones and stories of the losses experienced by others. As someone with a lifelong commitment to social work, I see unlimited potential from my colleagues to come together, connect with and deliver high-quality services, and ultimately combat the opioid epidemic in the years to come.

Practical Strategies for Social Workers to Combat the Opioid Epidemic

ATTC Network Related Resources

ATTC Educational Packages for Opioid Use Disorders

The ATTC Network designed three competency-based guides to raise awareness of resources available to build the capacity of the workforce to address the opioid crisis. The digital guides are relevant to psychologists, counselors, social workers, peer support workers, and other behavioral health professionals who intersect with people at risk for misuse of, or who are already misusing, opioids.

Click here to review the ATTC Educational Package for Opioid Use Disorders-Social Workers.

References

Amato, L., Davoli, M., Perucci, C.A., Ferri, M., Faggiano, F., & Mattick, R.P. (2005). An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: Available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(4), 321-329.

American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) (2015). The ASAM national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. Retrieved from: https://www.asam.org/resources/guidelines-and-consensus-documents/npg

Andrilla, C.H.A., Coulthard, C., & Larson, E.H. (2017). Barriers rural physicians face prescribing buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Annals of Family Medicine, 15(4), 359-362.

Barlow, D. (2014). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (5th edition). Guilford Press, New York City, NY.

Bowen, E.A., & Walton, Q.L. (2015). Disparities and the social determinants of mental health and addictions: Opportunities for multifaceted social work response. Health & Social Work, 40(3), e59-e65.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2000). Comprehensive Case Management for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 27. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4215. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Retrieved from: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma15-4215.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics (2019). Drug overdose mortality by state. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics (2019). Drug overdose deaths. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html

Clemans-Cope, L., Epstein, M., & Wissoker, D. (2018). County-level estimates of opioid use disorder and treatment needs in California. The Urban Institute.

Dick, A.W., Pacula, R.L., Gordon, A.J., Sorbero, M., Burns, R.M., Leslie, D.L., & Stein, B.D. (2015). Increasing potential access to opioid agonist treatment in US treatment shortage areas. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(6), 1028-1034.

Hedegaard, H., Miniño, A.M., & Warner, M. (2018). Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db329.htm

Jones, C.M., Campopiano, M., Baldwin, G., & McCance-Katz, E. (2015). National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 1055(8), e55-e63.

Knopf, A. (2017). Ryan Haight Act stands in way of buprenorphine telehealth. Alcohol Drug Abuse Weekly, 29(33), 7-8.

Lister, J.J. (2017). The opioid crisis is at its worst in rural areas. Can telemedicine help? The Conversation. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/the-opioid-crisis-is-at-its-worst-in-rural-areas-can-telemedicine-help-86598

Lister, J.J., Brown, S., Greenwald, M.K., & Ledgerwood, D.M. (2019). Gender-specific predictors of methadone treatment outcomes among African Americans at an urban clinic. Substance Abuse.

Lister, J.J., Greenwald, M.K., & Ledgerwood, D.M. (2017). Baseline risk factors for drug use among African-American patients during first-month induction/stabilization on methadone. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 78, 15-21.

Lister, J., Weaver, A., Ellis, J., Ledgerwood, D., & Himle, J. (2019). Availability of medication-assisted treatment in rural Michigan. A comparison of non-metropolitan and metropolitan counties. Podium presentation at the 23rd Annual Conference of the Society for Social Work and Research, San Francisco, CA.

Mattick, R.P., Breen, C., Kimber, J., & Davoli, M. (2014). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD002207.

Powell, K.G., Treitler, P., Peterson, N.A., Borys, S., & Hallcom, D. (2019). Promoting opioid overdose prevention and recovery: An exploratory study of an innovative intervention model to address opioid abuse. International Journal of Drug Policy, 64, 21-29.

Salamanina, G., Diecidue R., Vigna-Taglianti, F., Jarre, P., Schifano, P., Bargagli, A.M.,…The VEdeTTE Study Group (2010). Effectiveness of therapies for heroin addiction in retaining patients in treatment: Results from the VEdeTTE Study. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(12), 2076-2092.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2018). Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2016). Naltrexone. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/naltrexone

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2019). Qualify for a practitioner waiver. Retrieved from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/buprenorphine-waiver-management/qualify-for-practitioner-waiver

Uehara, E. S., Barth, R. P., Olson, S., Catalano, R. F., Hawkins, J. D., Kemp, S., Nurius, P. S., Padgett, D. K., & Sherraden, M. (2014). Identifying and tackling grand challenges for social work (Grand Challenges for Social Work Initiative Working Paper No. 3). Baltimore, MD: American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare.

Workers, N. A. (2008). NASW Code of Ethics (Guide to the Everyday Professional Conduct of Social Workers). Washington, DC: NASW.

World Health Organization. The selection and use of essential medicines: report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2017 (including the 20th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 6th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 (WHO technical report series; no. 1006). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/trs-1006-2017/en/