Studies indicate that chronic pain and substance use disorders (SUDs) frequently co-occur (Chelminski et al., 2005; Rosenblum et al., 2003; Savage, Kirsh, & Passik, 2008); as such, addiction counselors who are knowledgeable about pain issues can provide better care for clients challenged by the need for assistance with pain control as well as substance abuse or dependence. This issue of the ATTC Messenger provides a basic overview of how pain and addiction can intersect and overlap. Much of the information derives from SAMHSA’s TIP 54 “Managing Chronic Pain in Adults With or in Recovery from Substance Use Disorders .”Comorbid chronic pain and SUDs require collaborative care including behavioral health, primary care, and often physical or occupational therapy and a consultation with pharmacy. Contributing to significant health care costs and misuse of services, these conditions will certainly demand that primary care and behavioral health rethink the current silos in which they operate as payment and systems reform unfold.

Chronic pain and addiction have many shared neurophysiological patterns. Most chronic pain involves abnormal neural processing. Similarly, addiction results when normal neural processes, primarily in the brain’s memory, reward, and stress systems, are altered into dysfunctional patterns. A full understanding of each condition is still emerging, and there is much to be learned about these conditions and their etiology, course of development, patterns of severity, interactions, and response to treatment.

Chronic pain and addiction are not static conditions. Both fluctuate in intensity over time and under different circumstances often require ongoing management. Treatment for one condition can support or conflict with treatment for the other; a medication that may be appropriately prescribed for a particular chronic pain condition may be inappropriate given the patient’s substance use history.

Chronic pain and substance use disorders (SUDs) also have similar physical, social, emotional, and economic effects on health and well being (Green, Baker, Smith, & Sato, 2003). Patients with one or both of these conditions may report insomnia, depression, impaired functioning, and other symptoms. Effective chronic pain management in patients with or in recovery from SUDs must address both conditions simultaneously (Trafton, Oliva, Horst, Minkel, & Humphreys, 2004).

Pain and responses to it are shaped by culture, temperament, psychological state, memory, cognition, beliefs and expectations, co-occurring health conditions, gender, age, and other factors. Because pain is both a sensory and an emotional experience, it is by nature subjective. Pain may be acute (e.g., postoperative pain), acute intermittent (e.g., migraine headache, pain caused by sickle cell disease), or chronic (persistent pain that may or may not have a known etiology). These categories are not mutually exclusive; for example, acute pain may be superimposed on chronic pain.

Continued pain can trigger emotional responses, including sleeplessness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, which in turn produce more pain. Such feedback cycles may continue to cause pain after the physiological causes have been addressed. Several studies show that the outcome of pain treatment is worse in the presence of depression, or when depression does not respond to treatment, and that the future course of pain syndromes can be, in part, predicted by emotional status (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2012). Physical inactivity and a lack of engagement with life may also lead to increased levels of anxiety, depression, and an increased risk for suicidal ideation; this may in turn lead a person to use substances in an attempt to treat themselves.

If use of a prescription pain medication (i.e. opioid analgesics) results in physical dependence, the person may experience increased pain when the substance is absent along with withdrawal symptoms (e.g., anxiety, nausea, cramps, insomnia). Withdrawal symptoms may lead to an increase in symptoms of depression and an increase in the potential risk for suicide. Ingesting more of the drug that caused the dependence relieves many of these symptoms. A similar situation may occur if the drug is one that elicits rebound symptoms. For example, ergot relieves migraines, but excessive use leads to rebound headaches that are more persistent and treatment resistant than were the original headaches.

In some people, a cycle develops in which pain or distress elicits severe preoccupation with the substance that previously provided relief. This cycle—seeking pain relief, experiencing relief, and then having pain recur—can be very difficult to break, even in the person without an addiction, and the development of addiction markedly exacerbates the difficulty.

Addiction to prescription pain medication is widely misunderstood and part of working with chronic pain sufferers is helping to educate them. Below are two common misunderstandings that your clients may hold:

1. “If I need higher doses or have withdrawal symptoms when I quit, I’m addicted.”

Many people mistakenly use the term “addiction” to refer to physical dependence. That includes doctors. "Probably not a week goes by that I don’t hear from a doctor who wants me to see their patient because they think they’re addicted, but really they’re just physically dependent,”said Scott Fishman, MD, professor of anesthesiology and chief of the division of pain medicine at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine, interviewed for an article on WebMD. In the same article, Susan Weiss, PhD, chief of the science policy branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse notes, “Physical dependence, which can include tolerance and withdrawal, is different. It’s a part of addiction but it can happen without someone being addicted.” She adds that if people have withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking their pain medication, "it means that they need to be under a doctor’s care to stop taking the drugs, but not necessarily that they’re addicted”(Hitti, 2011).

2. “Everyone gets addicted to pain drugs if they take them long enough.”

“The vast majority of people, when prescribed these medications, use them correctly without developing addiction,” said Marvin Seppala, MD, chief medical officer at the Hazelden Foundation (Hitti, 2011).

Dr. Weiss elaborates more about the complexities, commenting, “I think where it gets really complicated is when you’ve got somebody that’s in chronic pain and they wind up needing higher and higher doses, and you don’t know if this is a sign that they’re developing problems of addiction because something is really happening in their brain that’s ... getting them more compulsively involved in taking the drug, or if their pain is getting worse because their disease is getting worse, or because they’re developing tolerance to the painkiller”(Hitti, 2011).

Providing pain control for the 5% to 17% of the U.S. population with a substance abuse disorder presents primary care physicians with unique challenges that may be helpful for addiction counselors to understand. These include:

Further, most doctors do not have much training in addiction, or in pain management for that matter. Most addiction counselors do not have much training in pain management. Working together may be key for successfully treating patients.

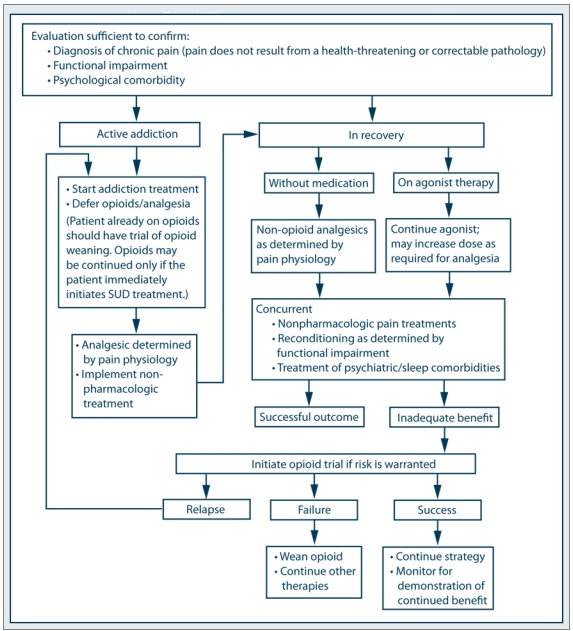

SAMHSA’s TIP 54 (as noted previously) presents a consensus panel’s recommended strategy for treating chronic pain in adults who have or are in recovery from a substance use disorder.

Collateral information is an important part of the assessment of pain treatment in primary care, as it is with addiction treatment. Clinicians should communicate with families, pharmacists, addictions counselors and other clinicians, after the patient has given consent. If the patient declines to give consent, prolonged treatment with controlled pain medications may be contraindicated. Collateral information also helps protect the patient from misusing medications.

Addiction counselors should keep in mind that several factors may complicate a physician’s assessment of pain levels:

Each of these challenges may be addressed with clinic policies and procedures for comprehensive and regular assessment, improved provider patient communication, and collaborative care protocols allowing the PC providers to interact with the behavioral health staff and counselors. Clinicians must assess all patients who have chronic pain at regular intervals because treatment needs can change. For example, a patient may develop tolerance to a particular opioid, or the underlying disease condition may change or worsen.

In a recovering individual, the fear of experiencing withdrawal can be a substantial block to successful discontinuation of medication when it is no longer needed for pain control. Successful management of these concerns may be accomplished by slowly tapering medications over several days under close supervision as well as working with a pain and/or addiction medicine specialist who is able to suggest alternate pharmacotherapy that isn’t addictive to help manage the withdrawal. In certain cases, short-term admission to a detoxification unit may be necessary.

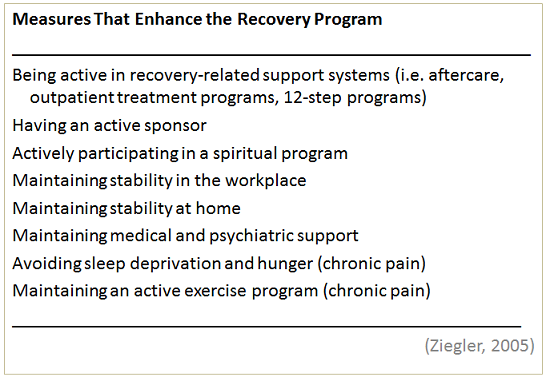

Recovering alcoholics and addicts in pain can be treated safely. Below are some guidelines from “Addiction and the Treatment of Pain” by Peggy Ziegler published in Substance Use and Misuse:

Acute pain (postoperative pain, following trauma, after dental work)

Chronic pain presents different and perhaps more challenging management situations, which can best be addressed within a collaborative care model.

(Ziegler, 2005)

Clearly, in dealing with the complexities outlined above, providers who adhere to a collaborative care model are going to be much more effective and provide better care for their patients. Without a team approach, patients may be exposed to inconsistent, duplicative, or even contraindicated, care.

What happens if a person becomes dependent upon painkillers—how is that best treated? “The “standard treatment” for prescription opioid dependence is evolving, and I can’t say that there is a single current standard at this time,” says Roger Weiss, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, MA. Weiss was the lead author of the first—and so far only—large-scale study of the treatment of prescription opioid addiction, which posed as many questions as it answered (Holmes, 2012).

At present, many patients addicted to opioids who seek treatment are tapered off the drugs and given behavioral treatment alone, or are otherwise maintained on buprenorphine or methadone. “In our study, even those who were maintained on buprenorphine for 12 weeks had successful outcomes in only approximately half of the cases”, says Weiss, while behavioral treatment after tapering off opioid drugs “did not result in good outcomes. Most patients who tapered off of buprenorphine did return to opioid use,” Weiss explains. “I believe that this shows that for many such patients, ongoing pharmacotherapy may be highly beneficial in sustaining recovery. We are currently conducting a longer-term follow up study which should give us greater insight into the types of treatments that would be necessary to sustain longer-term recovery.” One such option could be naltrexone, an opioid receptor antagonist. Although poor adherence to oral naltrexone has limited its success in the past, an injectable extended release formulation is available. “We will see what role long-lasting injectable naltrexone has in the treatment of this population,” Weiss affirms (Holmes, 2012).

“I think that recovery from prescription opioid dependence is likely best achieved through a combination of pharmacotherapy and counseling,” concludes Weiss; “determining the optimal combination of these two treatment approaches is an evolving field.”(Holmes, 2012).

Chronic pain management is often complex and time consuming. The effectiveness of multiple interventions is augmented when all medical and behavioral healthcare professionals involved collaborate as a team (Sanders, Harden, & Vicente, 2005). Addiction specialists, in particular, can make significant contributions to the management of chronic pain in patients who have SUDs. They can: put safeguards in place to help patients take opioids appropriately; reinforce behavioral and self-care components of pain management; work with patients to reduce stress; assess patients’ recovery support systems, and identify relapse. The more complicated the case, the more beneficial a team approach becomes.

Sean Mackey, MD, PhD, Chief of the Pain Management Division at Stanford University and Associate Professor of Anesthesia and Pain Management states “A multidisciplinary approach is needed to treat patients in pain who have substance abuse issues.”

When treating patients with both chronic pain and a substance abuse disorder, Dr. Mackey advises making sure that they are receiving psychological counseling, either in a group or individually. “Many treatments we use in substance abuse overlap with chronic pain treatment—the psychological and behavioral skills are the same,” he says. (Vimont, 2011)

Author:

Wendy Hausotter, MPH - Research Associate, Northwest ATTC.