Erin L. Winstanley, Ph.D.

If not us, who? And if not now, when? –Ronald Regan

Hepatitis C (HCV), a blood-borne virus that infects the liver, is the “Silent Epidemic” that has been looming in the shadow of the opioid epidemic for more than a decade. In 2008, drug overdose became the leading cause of injury death in the United States (Paulozzi et al. 2012). A year earlier, the number of the deaths caused by HCV exceeded those caused by HIV (Ly et al. 2012). Individuals with HIV are now able to live significantly longer because of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and medications that can prevent HIV infection, yet these medications are not curative like those for HCV. Direct-acting antiretroviral (DAA) medications, taken once a day for 12 weeks, can eliminate the virus in ~95% of treated individuals. Those at great risk of HCV infection, however, may not realize the benefits of these life-sustaining medications.

An estimated 3.5 million Americans have HCV, yet only half are aware they are infected (Yehia et al. 2014). Injection drug use is the primary mode of HCV transmission in the U.S. (CDC 2001), and the majority of new cases are among young persons with injection drug use (PWID) who reside in non-urban areas (OHAIDP 2014). Notably, American Indians and Alaska Natives have the highest risk of HCV-related death, which has been attributed to significant treatment barriers (Reilley and Leston 2017). HCV treatment delivery can be daunting to programs and health systems that are already under-resourced and under-funded. Our fragmented health care system makes it difficult to provide integrated treatment for patients with co-occurring substance use disorders (SUD) and HCV. Individuals with a SUD may be reluctant to seek medical care in health care settings in which they have previously been treated with disdain (Volkow 2020) and, further, they may receive lower quality health care due to stigma (van Boekel et al. 2013).

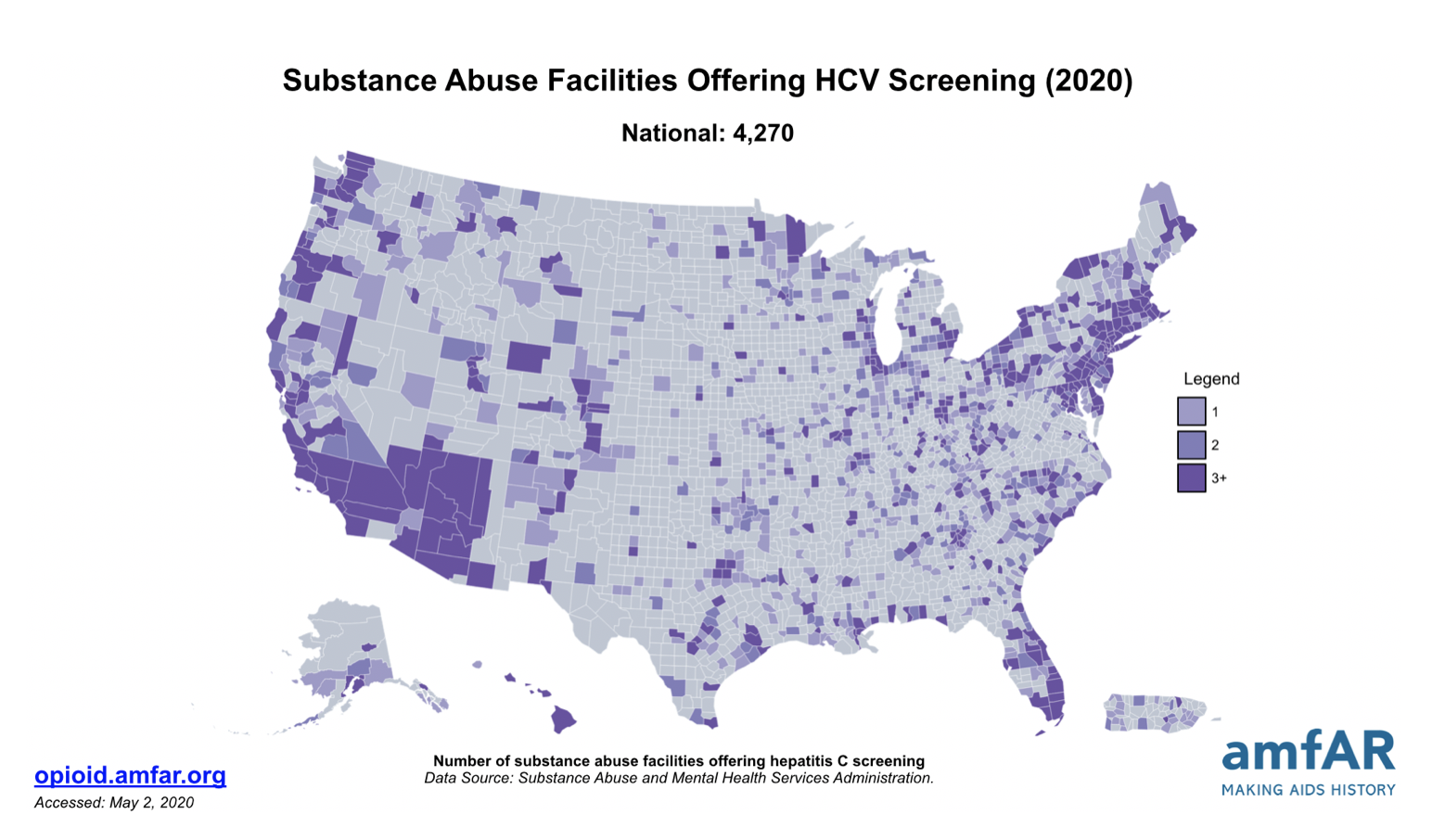

Unfortunately, only 28% of SUD treatment programs offer HCV services (Sayas et al. 2018). And whereas 61%-64% of federally certified opioid treatment programs (OTPs) provide some level of viral hepatitis services (Jones et al. 2019; Sayas et al. 2018), only 12% provide HCV treatment (Jones et al. 2019).

Approximately 42%-81% of patients treated in these settings have HCV and few receive treatment (Jimenez-Trevino et al. 2011; Hser et al. 2006; Norton et al. 2017). Significant geographic variations in HCV incidence can be partially explained by patterns of injection drug use. Individuals using methamphetamine and fentanyl may inject more frequently, increasing their risk of HCV infection, because these drugs have a shorter duration of effect. Methamphetamine use is increasing in the U.S. (Jones et al. 2019) and, globally, injection drug use of stimulants is estimated to be associated with 9-24% of HCV cases (Farrell et al. 2019).

SUD programs have legitimate concerns and reasons for not delivering HCV services. SUD programs often lack infrastructure and clinicians may not have sufficient HCV knowledge to feel confident delivering services (Talah et al. 2013). Individuals with chronic HCV often do not appear to be physically ill and most individuals are asymptomatic for decades until the effects of liver disease become evident (SAMHSA 2011). Consequently, delayed presentation of symptoms may lead clinicians and patients to believe that the virus is benign (Grebley et al. 2019). Another concern may be HCV reinfection, particularly among clients who are early in their recovery. Treatment of HCV not only prevents the development of liver disease, but if relapse to drug use occurs, then virus transmission will be prevented. An estimated 0-5% of treated individuals become re-infected; however, reinfection rates are four times lower among individuals receiving medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (Grebley et al. 2019). Evidence shows that clients retained in buprenorphine treatment have better HCV outcomes (Norton et al. 2017). SUD treatment programs, particularly those offering MOUD, are truly an ideal setting for HCV testing and treatment.

Integration of HCV Services into SUD Treatment

The ATTC Network Coordinating Office will be publishing “A Guide to Integrating HCV Services into Opioid Treatment Programs: Promising and Emerging Best Practices”. The guide provides practical resources including a brief overview of HCV testing and treatment, strategies to integrate HCV services into SUD treatment settings and tips on how to fund HCV service delivery. An iterative process was used to develop the guide that included a scoping review of the HCV literature and existing web-based resources, convening of a national Thought Leader panel and by conducting site visits with five SUD treatment programs that have integrated HCV services. The “Resource” section of the guide provides a condensed list of HCV web-based resources that are most relevant to SUD treatment providers, which ranges from online HCV trainings for health professionals to best practices for HCV counseling. The guide also presents providers real-world examples of how programs have integrated HCV services.

In the hierarchy of needs framework, reducing overdose deaths has been an immediate and justified priority given the magnitude of deaths. Nevertheless, we cannot lose sight of the long-term consequences of HCV and the importance of preventing transmission in the care settings, in which our patients feel most comfortable. The reluctance of SUD programs to integrate HCV services resonates with the reasons why some primary care physicians chose not to become waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. Dr. Provenzano, a primary care physician, penned a perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine expressing her regret that she was unable to fulfill her patient’s request to treat her opioid use disorder. She referred her patient elsewhere and later learned of her death, writing “Ms. L. and I had had a relationship. She had trusted me. And I’d turned her away.” The multidimensional health consequences of SUDs push clinicians outside of their silos and comfort zones. Even small steps toward integration, such as routine HCV screening, can be important and convey to patients that their lives are worth saving.

References:

Barocas, J.A. (2020). It’s not them, it’s us: Hepatitis C reinfection following successful treatment among people who inject drugs. Clinical infectious diseases, Mar 12; ciaa258.

doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa258. Online ahead of print.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance United States, 2011. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/2011Surveillance/PDFs/2011HepSurveillanceRpt.pdf. Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

Farrell, M., Martin, N.K., Stockings, E., et al. (2019). Responding to global stimulant use: challenges and opportunities. Lancet, 394(10209):1652–67.

Grebely, J., Hajarizadeh, B., Lazarus, J.V., Bruneau, J., Treloar, C., etc. (2019). Elimination of hepatitis C virus infection among people who use drugs: Ensuring equitable access to prevention, treatment, and care for all. International journal of drug policy, 72, 1-10.

Hser, Y., Stark, M.E., Paredes, A., Huang, D., Anglin, M.D., Rawson, R. (2006). A 12-year follow-up of a treated cocaine-dependent sample. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 30: 219-226.

Jimenez-Trevino, L., Saiz, P.A., Garcia-Portilla, M.P., Diaz-Mesa, E.M., Sanchez-Lasheras, F., Buron, P., et al. (2011). A 25-year follow-up of patients admitted to methadone treatment for the first time: Mortality and gender differences. Addictive behavior, 36: 1184-90.

Jones, C.M., Byrd, D.J., Clarke, T.J., Campbell, T.B., Ohuoha, C., McCance-Katz, E.F. (2019). Characteristics and current clinical practices of opioid treatment programs in the United States. Drug and alcohol dependence, 205: 107616.

Jones, C.M., Underwood, N., Compton, W.M. (2019). Increases in methamphetamine use among heroin treatment admissions in the United States, 2008-17. Addiction, 115: 347-353.

Ly, K.N., Xing, J., Klevens, R.M., Jiles, R.B., Ward, J.B., Holmberg, S.D. (2012). The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United Stated between 1999 and 2007. Annals of intern medicine, 156:271-8.

Norton, B.L., Beitin, A., Glenn, M., DeLuca, J., Litwin, A.H., Cunningham, C.O. (2017). Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 75: 38-42.

Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy (OHAIDP), Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Action Plan for the Prevention, Care & Treatment of Viral Hepatitis, Updated 2014-2016. Retrieved from http://aids.gov/pdf/viral-hepatitis-action-plan.pdf on April 22, 2014.

Paulozzi, L., Dellinger, A., Degutis, L. (2012). Lessons from the past. Injury prevention, 18:70.

Provenzano, A.M. (2018). Caring for Ms. L. – Overcoming my fear of treating opioid use disorder. New England journal of medicine, 378 (7): 600-601.

Reilley, B., Leston, J. (2017). A tale of two epidemics – HCV treatment among Native Americans and veterans. New England journal of medicine, 377(9): 801-803.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Addressing Viral Hepatitis in People with Substance Use Disorders. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 53. HHS publication No. (SMA) 11-4656. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011.

Sayas, A., McKay, S., Honermann, B., Blumenthal, S., Millett, G., Jones, A. (2018). Despite Infectious Disease Outbreaks Linked to Opioid Crisis, Most Substance Abuse FacilitiesDon’t Test for HVI or HCV. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20181002.180675/full/. Accessed August 7, 2019

Talah, A.H., Dimova, R.B., Seewald, R., Peterson, R.H., Zeremski, M., Perlman, D.C., Des Jarlais, D.C. (2013). Assessment of methadone clinic staff attitudes towards hepatitis C evaluation and treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 44(1): 115-119.

Van Boekel, L.C., Brouwers, E.P.M., van Weeghel, J., Garretsen, H.F.L. (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug and alcohol dependence, 131:23-35.

Volkow, N.D. (2020). Stigma and the toll of addiction. New England journal of medicine, 382 (14): 1289-1290.

Yehia, B.R., Schraz, A.J., Umscheid, C.A., Lo Re, V. III. (2014). The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis c virus infection in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(7): e101554.