By Jamey Lister, PhD, Mark van der Maas, PhD, & Lia Nower, JD, PhD

Center for Gambling Studies

School of Social Work

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

An overview on issues facing gambling disorder within the field of addiction

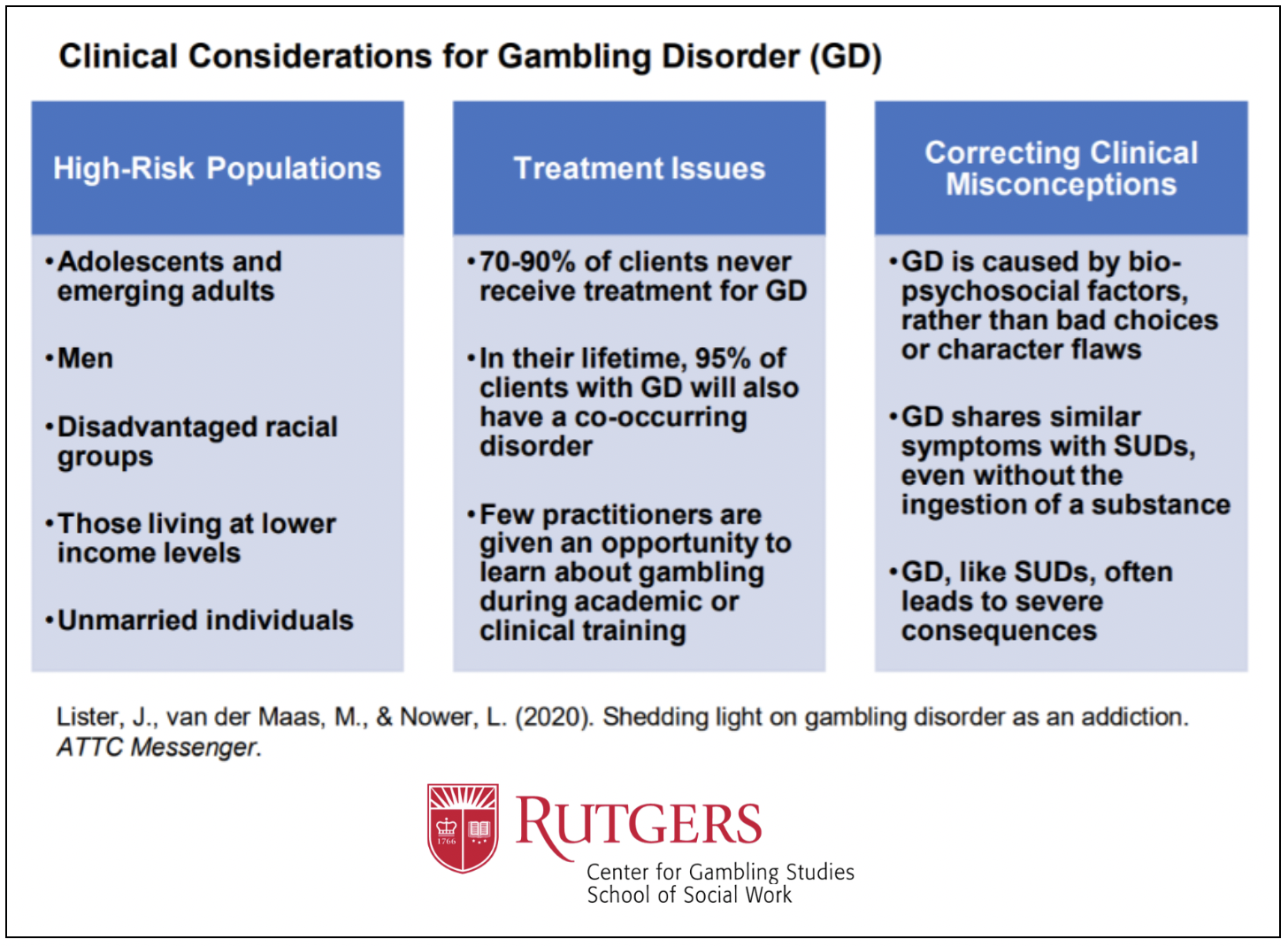

Gambling disorder is the only behavioral addiction recognized by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013), joining substance use disorders (SUDs) that arise from problems with legal (e.g., alcohol, tobacco), illegal (e.g., cocaine, heroin), or prescribed substances (e.g., pain and sedative medications). Although it overlaps with SUDs in many ways, it is the only addiction that does not require ingesting a substance and has key distinguishing criteria such as “chasing” (returning to gamble to recoup losses) and “bailouts” (relying on others to alleviate financial consequences of gambling). These differences have fueled misunderstandings among practitioners and researchers about the fit of behavioral addictions with other substance-based addictions (Petry, Zajac, & Ginley, 2018). Furthermore, few practitioners screen for gambling when they screen for SUDs, severely limiting the identification and treatment of gambling disorder (Loy et al., 2018), despite the potential for gambling to trigger relapse to SUDs given the high rates of comorbidity (Bischof et al., 2013; Dash et al., 2019; Kessler et al., 2008).

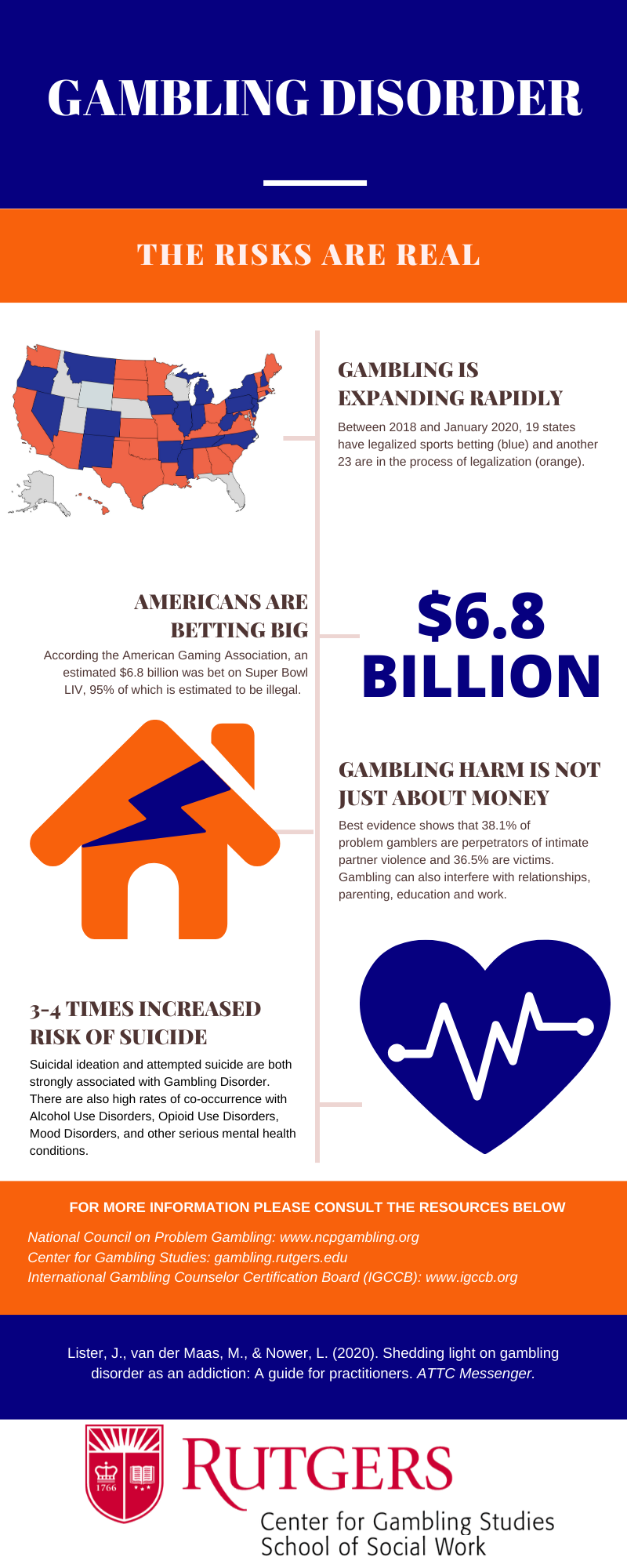

Efforts to educate practitioners are additionally hampered by the lack of dedicated federal funding in the U.S. for prevention, education, research or treatment of gambling disorder. A majority of the research in the area emerges from countries such as Canada and Australia, which have governmental offices committed to addressing excessive gambling and gambling-related harm (Weinstock, 2018). Similarly, practitioners rarely encounter information about gambling disorder during their educational and clinical training on addiction, which typically focuses exclusively on substances (Rogers, 2013). As a result, many practitioners may adapt SUD treatments as their first option when addressing the needs of clients with gambling disorder (Rash, Weinstock, & Van Patten, 2016), likely due to their lack of access to information specific to gambling disorder (Hodgins, Stea, & Grant, 2011). The lack of trained practitioners in the U.S. is of particular concern given the recent expansion of legalized sports betting and online gambling opportunities. At the start of 2020, there were 20 states and Washington, D.C. that have legalized sports betting, and another 23 reviewing bills for legalization in the near future. The American Gaming Association estimates that roughly $6.8 billion USD was wagered on the 2020 Super Bowl alone, with 95% of those bets placed illegally (O’Brien, 2020; Rodenberg, 2019). In New Jersey (where the authors reside), a disproportionate number of those who wager on sports are emerging adults (Nower, Volberg, & Caler, 2018), and the anonymity of online wagering heightens the risk that adolescents will gamble using their parents’ accounts.

To help practitioners who may feel unprepared to treat gambling addiction, we describe important facts, provide an overview of best practice approaches for assessment and treatment, and outline options to help practitioners build capacity for gambling disorder services in their setting.

What do practitioners need to know about gambling disorder?

Similar to substance-based addictions, people who develop gambling addiction generally experience a combination of risk factors. These include characteristics such as adverse childhood experiences, mood disorders, coping with stress through avoidant behaviors, and personality traits toward impulsivity and risk taking (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Vitaro et al., 2019). Rarely do people with gambling disorder only experience problems related to gambling, as estimates suggest approximately 95% also meet criteria for one or more co-occurring psychiatric disorders in their lifetime (Bischof et al., 2013). As a result, many people use gambling as a means of coping with psychiatric symptoms, such as trauma and depression (Ledgerwood & Milosevic, 2015; Lister, Milosevic, & Ledgerwood, 2015; Takamatsu, Martens, & Arterberry, 2016). This can be especially problematic for suicide risk, a psychiatric complication that is approximately 3-4 times higher for problem gamblers compared to the general population (Moghaddam et al., 2015; Newman & Thompson, 2003). For example, one study of 342 clients in treatment for gambling disorder found that 49% had a history of suicidal ideation or attempt (Petry & Kiluk, 2002).

Gambling exists on a spectrum, from those who gamble but experience no problems to those who develop consequences and symptoms of gambling disorder. On average, 3-4% of adults will experience gambling problems during their lifetime (Gerstein et al., 1999; Kessler et al., 2008; Rash et al., 2016). The prevalence of gambling disorder is higher among specific groups, including people living at lower incomes, men, adolescents and emerging adults, unmarried individuals, and people from marginalized racial groups (Kessler et al., 2008; Petry, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Welte et al., 2001). The addiction often leads to increased rates of unemployment, homelessness, family violence, medical and mental health problems, incarceration, and intergenerational addiction (Dowling et al., 2016; Nower, Mills, & Li 2020). Across all populations, there are considerable barriers to accessing gambling treatment (Khayyat-Abuaita, et al., 2015; Ledgerwood & Lister, 2015; Pulford et al., 2009). These barriers, in part, explain why only 10-30% of people with gambling disorder ever receive gambling treatment during their lifetime (Slutske et al., 2006, Suurvali et al., 2009).

Despite a sizable body of research, many misconceptions about gambling addiction persist and influence the low rates of treatment-seeking by stigmatizing beliefs about those with gambling problems (e.g., “having poor character”) (Hing, Nuske, Gainsbury, & Russell, 2016; Hing, Russell, Gainsbury, & Nuske, 2016). A few common false messages include, “Quitting gambling is easier than other addictions because there’s no dependence”; “Many people gamble, so those with problems just make bad choices”; and, “If we label gambling as an addiction, we might as well call every behavior an addiction.” Some of these myths overlap with those seen in other SUDs (Lister, 2019), while others are unique to gambling. Despite a lack of physical dependence, research has shown that gambling disorder is related to brain behavior changes, making increasingly large bets over time, and withdrawal that is comparable to SUDs (Blaszczynski, et al 2008; Lee et al., 2020). While it is true that published rates of gambling disorder are not as high as for other legal substances (Rash et al., 2016), the actual rates are likely unknown due to underreporting and a lack of adequate screening by an educated workforce. In addition, it is plausible more people will experience gambling problems as opportunities expand through online access on mobile phones and live, in-game wagering at sporting events. It is critical for practitioners to be fully informed about gambling disorder to combat these narratives. Once they are, they can use this information as they learn about assessment and treatment approaches.

What clinical strategies can practitioners use to help people with gambling disorder?

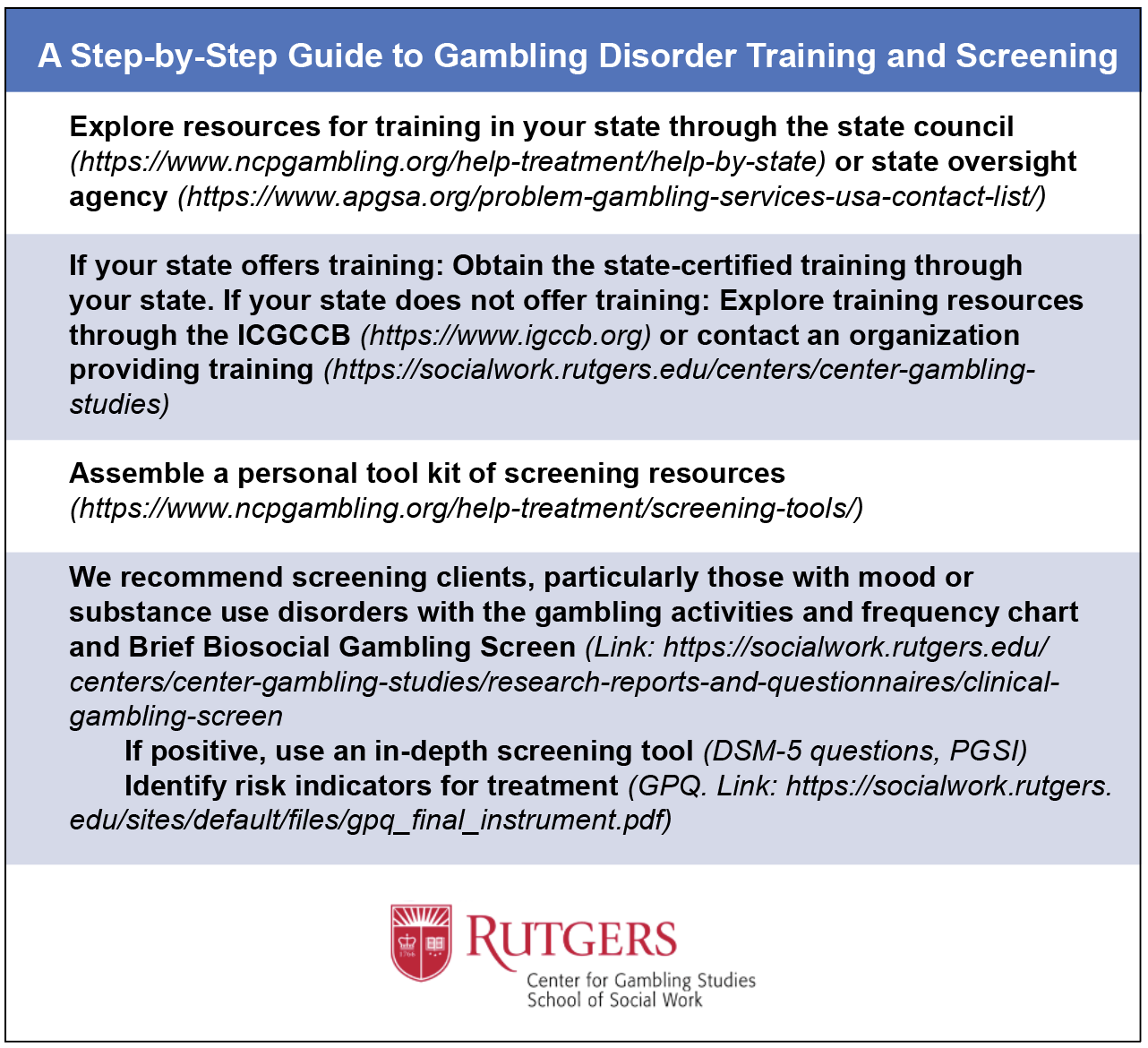

There are a few concrete approaches we recommend practitioners use to improve treatment outcomes for clients with gambling disorder. These include screening all clients for gambling disorder, obtaining specialized training in gambling disorder treatment, and developing skills to deal with the complex array of problems clients with gambling disorder often encounter. Assessment should include initial screening for the frequency of specific gambling activities. Of note, due to the stigma associated with problem gambling, we recommend asking about specific gambling behaviors (e.g., lottery, bingo, sports betting, raffles, casino wagering, online betting), as opposed to simply asking whether clients “gamble” since many may feel stigmatized about gambling. If a client reports gambling activities, the practitioner should follow up with a brief screening tool for problem gambling severity, such as the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS, Gebauer et al., 2010) or the National Opinion Research Center DSM-IV Screen for Gambling Problems (NODS-PERC, Volberg, Munck & Petry, 2011). Practitioners can also administer the DSM-5 questions about gambling disorder or use a self-report measure such as the PGSI (Ferris & Wynne, 2001). Finally, practitioners can use the Gambling Pathways Questionnaire (GPQ, Nower & Blasczcynski, 2017) to identify key risk factors to target in treatment to assist in maintaining recovery.

While screening is imperative, it is critical to train practitioners to provide gambling treatment. Providers without specialized training may be ill-equipped to address gambling-related cognitions, financial and legal problems, betting systems for specific gambling activities, or other features of the disorder. They may also mistakenly believe adapting SUD treatment for gambling disorder is adequate for a successful outcome, but fail to recognize the unique and specialized knowledge needed to address gambling-specific beliefs, misguided betting strategies, and etiological risk factors that are key to successful recovery. Ideally, practitioners should attend 30 hours of training, approved by the International Gambling Counselor Certification Board (IGCCB) of the National Council on Problem Gambling in Washington, D.C. Many states offer not only free training but also state-sponsored treatment for gambling with reimbursement to credentialed providers.

Practitioners following best practices for assessment and treatment options can also enhance client outcomes by gaining training in evidence-based approaches for common co-occurring SUDs (Daley & Marlatt, 2006) and emotional disorders (Beck, 1979). In addition, practitioners can refer clients to other helpful services such as financial counseling, considering the substantial proportion of problem gamblers in debt or bankruptcy (Swanton et al., 2020). Providing counseling or support through online systems is an additional and effective way to increase access for those who might be less likely to seek counseling due to restrictions on time, distance, finances, and/or fear of stigma (van der Maas et al. 2019). Recent advancements in information technologies can also be used to help clients avoid or limit gambling activities. Personal computer or mobile phone applications (e.g., Gamban) exist that allow a client to block themselves from gambling websites, record journals outlining where and when the client feels the urge to gamble, and even provide assessments and self-directed therapy (Griffiths, 2018; Pfund et al., 2019).

How might practitioners build capacity for gambling disorder services?

Many practitioners may feel that building capacity for services in their setting is unlikely. Reasons may include funding constraints in their agency to expand services, an inability to reimburse for gambling disorder services, or negative attitudes and myths about gambling among colleagues and supervisors in their setting. We suggest practitioners encountering these obstacles connect with resources in their state as well as the IGCCB, which credentials gambling counselors, and attend annual meetings to build coalitions and local solutions. Practitioners looking to engage with community settings are encouraged to build partnerships with gambling venues and provide trainings to their staff around harm reduction and treatment resources the venue can provide to patrons in need of care (Oehler et al 2017). Furthermore, we recommend that trained gambling practitioners connect with university training programs providing education on addictions. As few universities have gambling-specific curriculum, these practitioners could develop courses or connect with established curriculum. At Rutgers, for example, we have initiated the first ICB-certified training for Master’s students in social work as well as community providers, which will soon be offered online in and outside New Jersey. In addition, practitioners who build relationships can help facilitate collaborations with gambling researchers (e.g., Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University School of Social Work).

Conclusions

Gambling addiction is a devastating disorder that harms not only individuals but families and communities. It often co-occurs with SUDs and emotional disorders but is seldom identified in treatment settings, because practitioners are not trained to recognize or treat it. The continued expansion of gambling opportunities makes it critical to develop a trained and competent network of treatment professionals in every state. Practitioners can assist in building capacity to treat this disorder by actively seeking out available resources, encouraging screening clients in their agencies, and obtaining the necessary specialized training to competently treat clients who have moved from recreational to problem gambling.

The authors would like to thank all members of the Center for Gambling Studies at Rutgers University School of Social Work for their input and suggestions.

Correspondence should be addressed to Jamey Lister ([email protected]), Mark van der Maas ([email protected]), and Lia Nower ([email protected]).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Beck, A. T. (Ed.). (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford press.

Bischof, A., Meyer, C., Bischof, G., Kastirke, N., John, U., & Rumpf, H. J. (2013). Comorbid Axis I-disorders among subjects with pathological, problem, or at-risk gambling recruited from the general population in Germany: Results of the PAGE study. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1065-1070.

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487-499.

Blaszczynski, A., Walker, M., Sharpe, L., & Nower, L. (2008). Withdrawal and tolerance phenomenon in problem gambling. International Gambling Studies, 8(2), 179-192.

Daley, D. C., & Marlatt, G. A. (2006). Overcoming your alcohol or drug problem: Effective recovery strategies workbook (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Dash, G. F., Slutske, W. S., Martin, N. G., Statham, D. J., Agrawal, A., & Lynskey, M. T. (2019). Big Five personality traits and alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and gambling disorder comorbidity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 420.

Dowling, N., Suomi, A., Jackson, A., Lavis, T., Patford, J., Cockman, S., ... & Harvey, P. (2016). Problem gambling and intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(1), 43-61.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Gebauer, L., LaBrie, R., & Shaffer, H. J. (2010). Optimizing DSM-IV-TR classification accuracy: A brief biosocial screen for detecting current gambling disorders among gamblers in the general household population. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(2), 82-90.

Gerstein, D., Volberg, R. A., Toce, M. T., Harwood, H., Johnson, R. A., Buie, T., & Sinclair, S. (1999). Gambling impact and behavior study: Report to the national gambling impact study commission. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center.

Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Hot topics in gambling: gambling blocking apps, loot boxes, and 'crypto-trading addiction'. Online Gambling Lawyer, 17(7), 9-11.

Hing, N., Nuske, E., Gainsbury, S. M., & Russell, A. M. (2016). Perceived stigma and self-stigma of problem gambling: perspectives of people with gambling problems. International Gambling Studies, 16(1), 31-48.

Hing, N., Russell, A. M., Gainsbury, S. M., & Nuske, E. (2016). The public stigma of problem gambling: Its nature and relative intensity compared to other health conditions. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 847-864.

Hodgins, D. C., Stea, J. N., & Grant, J. E. (2011). Gambling disorders. The Lancet, 378(9806), 1874-1884.

Khayyat-Abuaita, U., Ostojic, D., Wiedemann, A., Arfken, C. L., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2015). Barriers to and reasons for treatment initiation among gambling help-line callers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(8), 641-645.

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., & Shaffer, H. J. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 38(9), 1351-1360.

Ledgerwood, D.M., & Lister, J.J. (2015). Why don’t problem gamblers seek treatment? A few possible reasons. International Centre for Youth Gambling Problems and High-Risk Behaviors Newsletter, 15(3), 1-3.

Ledgerwood, D. M., & Milosevic, A. (2015). Clinical and personality characteristics associated with post traumatic stress disorder in problem and pathological gamblers recruited from the community. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(2), 501-512.

Lee, L., Tse, S., Blaszczynski, A., & Tsang, S. (2020). Concepts and controversies regarding tolerance and withdrawal in gambling disorder. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 31, 54-59.

Lister, J.J. (2019). Practical strategies for social workers to combat the opioid epidemic. ATTC Messenger. Published by the Addiction Technology Transfer Center network, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Lister, J.J., Milosevic, A., & Ledgerwood, D.M. (2015). Psychological characteristics of problem gamblers with and without mood disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(8), 369-376.

Loy, J. K., Grüne, B., Braun, B., Samuelsson, E., & Kraus, L. (2018). Help-seeking behaviour ofproblem gamblers: a narrative review. Sucht, 64, 259-272.

Moghaddam, J. F., Yoon, G., Dickerson, D. L., Kim, S. W., & Westermeyer, J. (2015). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in five groups with different severities of gambling: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(4), 292-298.

Newman, S. C., & Thompson, A. H. (2003). A population-based study of the association between pathological gambling and attempted suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(1), 80-87.

Nower, L., & Blaszczynski, A. (2017). Development and validation of the Gambling Pathways Questionnaire (GPQ). Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 95.

Nower, L., Mills, D., & Lee, W. (2020). Gambling Disorder: The First Behavioral Addiction. In Begun, A.L. & Murray, M., editors, The Routledge Handbook of Social Work and Addictive Behaviours.

Nower, L., Volberg, R.A. & Caler, K.R. (2017). The Prevalence of Online and Land‐Based Gambling in New Jersey. Report to the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. New Brunswick, NJ: Authors.

O’Brien, S. (2020). Super Bowl betting is expected to be $6.8 billion: The IRS will want a piece of your winnings. CNBC. Retrieved February 18, 2020 from https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/31/super-bowl-betting-to-be-6point8-billion-irs-wants-piece-of-winnings.html

Oehler, S., Banzer, R., Gruenerbl, A., Malischnig, D., Griffiths, M. D., & Haring, C. (2017). Principles for developing benchmark criteria for staff training in responsible gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 167-186.

Petry, N. M., & Kiluk, B. D. (2002). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(7), 462.

Petry, N. M., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(5), 564-574..

Petry, N. M., Zajac, K., & Ginley, M. K. (2018). Behavioral addictions as mental disorders: to be or not to be?. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 399-423.

Pfund, R. A., Whelan, J. P., Meyers, A. W., Peter, S. C., Ward, K. D., & Horn, T. L. (2019). The Use of a Smartphone Application to Complete Therapeutic Homework in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Gambling Disorder: a Pilot Study of Acceptability and Feasibility. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 1-8.

Pulford, J., Bellringer, M., Abbott, M., Clarke, D., Hodgins, D., & Williams J. (2009). Barriers to help-seeking for a gambling problem: The experiences of gamblers who have sought specialist assistance and the perceptions of those who have not. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 33-48.

Rash, C. J., Weinstock, J., & Van Patten, R. (2016). A review of gambling disorder and substance use disorders. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 7, 3-13.

Rodenberg, R. (2019). United States of sports betting: An updated map of where every state stands. ESPN. Retrieved February 18, 2020 from https://www.espn.com/chalk/story/_/id/19740480/the-united-states-sports-betting-where-all-50-states-stand-legalization

Rogers, J. (2013). Problem gambling: a suitable case for social work?. Practice, 25(1), 41-60.

Slutske, W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two US national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(2), 297-302.

Suurvali, H., Cordingley, J., Hodgins, D.C., & Cunningham, J. (2009). Barriers to seeking help for gambling problems: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 407-424.

Swanton, T. B., Gainsbury, S. M., & Blaszczynski, A. (2019). The role of financial institutions in gambling. International Gambling Studies, 19(3), 377-398.

Takamatsu, S. K., Martens, M. P., & Arterberry, B. J. (2016). Depressive symptoms and gambling behavior: Mediating role of coping motivation and gambling refusal self-efficacy. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(2), 535-546.

van der Maas, M., Shi, J., Elton-Marshall, T., Hodgins, D. C., Sanchez, S., Lobo, D. S., ... & Turner, N. E. (2019). Internet-based interventions for problem gambling: Scoping review. JMIR Mental Health, 6(1), e65.

Vitaro, F., Dickson, D. J., Brendgen, M., Lacourse, E., Dionne, G., & Boivin, M. (2019). Longitudinal interplay between gambling participation and substance use during late adolescence: A genetically-informed study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(5), 457.

Volberg, R. A., Munck, I. M., & Petry, N. M. (2011). A quick and simple screening method for pathological and problem gamblers in addiction programs and practices. The American Journal on Addictions, 20(3), 220-227.

Weinstock, J. (2018). Call to action for gambling disorder in the United States. Addiction, 113(6), 1156-1158.