For several years after its 2011 FDA approval, there existed only one randomized controlled trial of XR naltrexone for opioid use disorder: a placebo-controlled trial conducted in Russia. In late 2017 and early 2018, results from two randomized controlled trials were published comparing the effectiveness of XR naltrexone with buprenorphine. This article aims to answer some very practical but difficult questions about XR naltrexone:

Part I of this article will cover the original Russian study, the controversy surrounding it, and key design choices that run through all three studies. Next month, Part II will cover the head-to-head trials. Part III will provide a summary perspective on all three medications and discuss policy implications of the XR naltrexone clinical trials.

In October 2010, XR naltrexone (Vivitrol®) was approved “for the prevention of relapse to opioid dependence, following opioid detoxification”. The approval was supported by a single industry-sponsored, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in Russia, a study that provoked considerable controversy in the research community. Opponents of the Russian study argued that XR naltrexone should have been subject to a non-inferiority trial with buprenorphine or methadone, medications that had already demonstrated effectiveness in decreasing illicit opioid use, disease transmission, and opioid-related deaths. The XR naltrexone researchers side-stepped this ethical requirement by conducting the study in Russia where buprenorphine and methadone are illegal. In defense of their design, the authors contended that many patients in the United States choose not to receive buprenorphine or methadone treatment or have contraindications. They proposed XR naltrexone as an alternative for these patients.

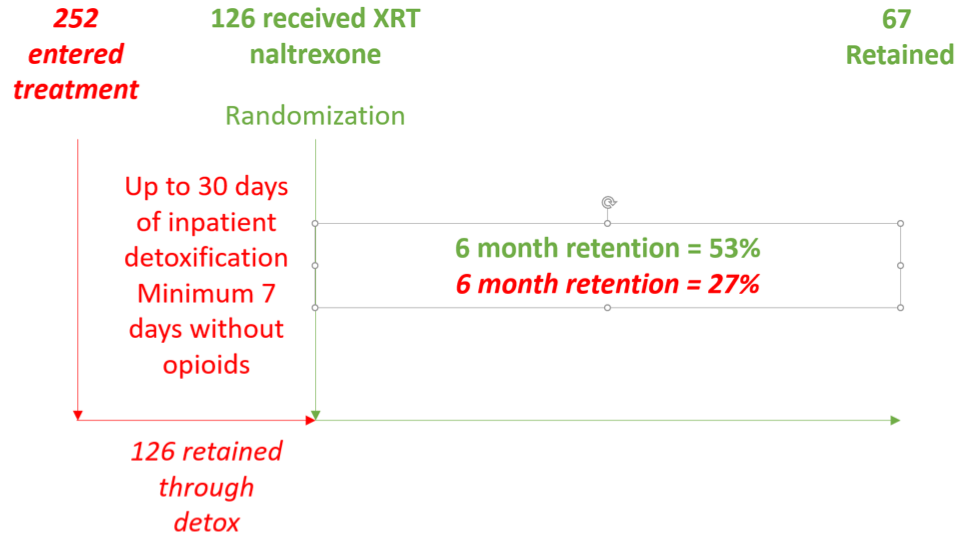

The architects of the Russian study made two design choices that were arguably more problematic than the choice of a placebo control. First, they excluded patients with high needs and lack of family support (Table 1); second, they randomized patients to XR naltrexone or placebo, not when they entered treatment, but only after they had successfully completed detoxification. To understand the importance of this second choice, imagine (or consider) that you are running a treatment program and are concerned about patient retention. You know that longer retention predicts higher rates of remission in patients with substance use disorders. You want to measure your retention rate, but instead of starting with patients who enter treatment, you only count patients who successfully complete detoxification. Those who drop out prior to full detoxification, you discount from your measure of retention; in effect, you pretend that these patients never showed up for treatment. Would measuring retention in this way be an accurate measure of your program’s effectiveness? This was precisely the design used in the Russian study. All patients received up to 30 days of inpatient detoxification but only those who achieved seven days without opioids were randomized to receive XRT naltrexone or placebo. Patients who dropped out of treatment were ignored.

For patients who were randomized to XR natlrexone, the six-month retention rate was 53%. At face value, this retention rate is comparable to the retention rates in buprenorphine studies. A study of low-threshold buprenorphine treatment in a New York City public hospital showed that over seven years, 57% of new opioid dependent patients were retained for six months. A study of African American patients in Baltimore showed that 58% of patients treated with buprenorphine were retained at six months. But these two studies measured retention from the moment a person presented to treatment. They had no exclusionary criteria that would decrease the external validity of their findings, and they did not discount patients who failed to transition to buprenorphine. In fact, 17% of patients dropped out of treatment during the first week of the New York program, but these failed inductions were included in the six-month measure of retention. The Baltimore researchers explained their commitment to studying treatment-as-usual: “Patients were recruited immediately after formal admission to treatment. Neither study was advertised in the community. Thus, study participants reflect the natural pool of new admissions at each of the treatment programs.”

|

|

Exclusions |

Retained 6 months |

|

XR naltrexone (Russia) |

|

53% |

|

Buprenorphine (New York) |

none |

57% |

|

Buprenorphine (Baltimore) |

none |

58% |

It is difficult to quantify the effect of excluding patients with significant mental and physical comorbidities, legal problems, and low social support; but clearly the remaining sample is not representative of the publicly funded treatment population. It is perhaps easier to quantify the proportion of persons expected to complete detoxification. In a study of 1,017 patients from 12 inpatient detoxification centers in Germany, successful detoxification from opioids ranged from 14 to 49% and averaged 34%. In a review of 55,056 detoxification episodes in California from 2006 to 2011, successful completion rates ranged from 45%-55%. More importantly, any agency that uses a detoxification protocol can calculate their own rate of success in fully detoxifying patients. Rates are generally quite low, and for that reason, the World Health Organization has specifically warned against encouraging medical detoxification in place of maintenance buprenorphine or methadone treatment.

For the sake of illustration, let’s be optimistic and assume that about 50% of persons with opioid dependence can successfully complete inpatient detoxification and be ready for an XR naltrexone injection. If the investigators in the Russian study had randomized patients at admission to inpatient treatment and 50% had successfully completed detoxification, the six-month retention rate would have been 27%, less than half what you would expect from a buprenorphine or methadone treatment protocol (Figure 1).

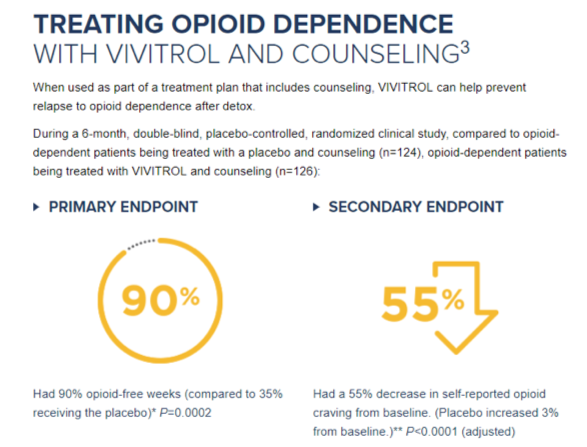

The Russian Study was an industry-sponsored clinical trial carefully designed to achieve FDA approval while avoiding the standard requirement that a new treatment be tested against existing treatments with known effectiveness. The chosen design exaggerates the perceived effectiveness of XR naltrexone through selection bias and renders the findings of low relevance to the population of Americans seeking treatment. Although XR naltrexone is only FDA approved for “for the prevention of relapse to opioid dependence, following opioid detoxification,” the maker of XR naltrexone (Alkermes) markets it more generally to patients with opioid dependence. In their 2010 press release, they wrote: “VIVITROL is now the first and only non-narcotic, non-addictive, once-monthly medication approved for the treatment of opioid dependence.” On their website, “detox” is mentioned but consumers are unlikely to understand how estimates of the drug’s effectiveness have been inflated by the company’s research design (Figure 2). Nowhere do patients receive information that buprenorphine and methadone are safer and more effective for patients physically dependent on opioids.

Next month: Next month, Part II of this article will cover the head-to-head trials, and Part III will provide a summary perspective on all three medications and discuss policy implications of the XR

naltrexone clinical trials.

Ned Presnall, LCSW, is executive director of Clayton Behavioral, an adjunct professor and senior data

analyst at Washington University in St. Louis, and a consultant for Missouri's Opioid State Targeted Response.

The opinions expressed in this article are the views of the author and do not reflect the position of the ATTC Network. No official support or endorsement of the ATTC Network for the opinions described in this article are intended or should be inferred.