Clinical and organizational practices that are culturally responsive are designed with services that are respectful of—and relevant to—beliefs, practices, cultural histories, preferred languages, health literacy levels, and communication needs of the diverse populations we serve.1 This overarching approach is consistent with the principal standard of the U.S. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Standards in Health and Health Care, commonly referred to as CLAS, which is to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities by establishing a blueprint for health and health care organizations to apply in their delivery of culturally responsive practices.2

The socioeconomic determinants of health, such as access and proximity to services, employment and housing stability, insurance status and other systemic barriers to accessing healthcare are also recognized for the profound impact they can have on behavioral health outcomes.3 For instance, indigenous people’s experience of colonialism, relocation, assimilation and loss of land and tribal customs have contributed to poor health outcomes for many Native American tribes throughout the United States and Canada.4

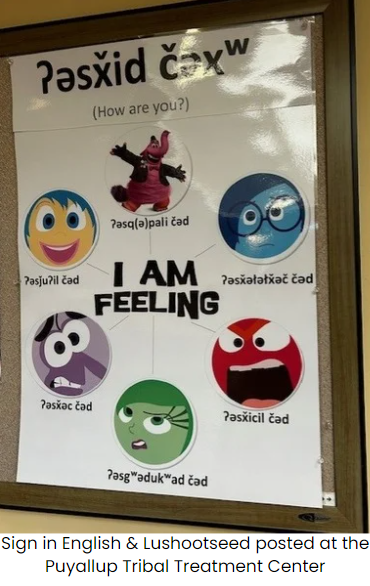

CLAS standards are used as principles to inform strategies designed to redress persistent health inequities. CLAS can be applied to a wide array of professions and sectors, including behavioral health, public health, social work, community health, medicine, emergency health, and more. Structural or service delivery adaptations are examples of applying CLAS. Ensuring there is linguistic interpretation when needed in counseling, or having signage or celebrations that encourage trust and safe places for different populations are examples of such adaptation.

Increasingly, practitioners are seeking to operate through a lens of cultural humility, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and others define as a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique that may encompass learning about another culture, and that also includes ongoing examination of one’s own bias or limited knowledge about another race, gender or other identity or cultural norm.5 Application of CLAS standards—together with process improvement strategies—can help organizations address and overcome the cultural, systemic, and communication barriers that many individuals face when seeking services.6,7

Just under half of the Federally Recognized Tribal Nations in the U.S. are located in Region 10 (AK, ID, OR, and WA). We endeavor to do the work to gain knowledge and understanding about the identities of the respective communities we are working in, and how they are shaped by their past and present environment. In doing so, we embrace cultural specificity and use of relevant cultural tools in combination with evidence-based practice. Many indigenous peoples have a strong preference for use of cultural practices which they perceive as authentic and relevant, especially those that they can trust, in tandem with other modalities. In practice, this means that service delivery and implementation may need to be further infused with cultural and linguistic standards to achieve better outcomes. In teaching Motivational Interviewing, for example, a tribal health authority may choose to make use of the Medicine Wheel or ensure that at least some of the learning materials are in the local, tribal language. Use of ceremony or smudging to open an event may also be incorporated in training, depending on the tribe(s) concerned.

Training programs and evaluation that draw on the strengths of tribal ways of knowing and being along with the strengths of Western knowledge work for the benefit of all. This indigenous learning is sometimes referred to as “Two-eyed seeing”, relying as it does on ancestral and cultural wisdom as well as more traditional Western approaches. Research has shown that implementing culturally responsive practices helps health workers adapt as needed and can lead to better health outcomes.8

Examples of targeted training and technical assistance from the Northwest ATTC that can be customized to suit the needs of unique populations:

Through intensive technical assistance, teams at behavioral health agencies are supported to identify 1-to-2 changes related to their service delivery or agency culture that they can implement over a period of time. Each agency is assisted to meet benchmarks they set for themselves. The process improvement or cultural change they focus on will vary: It may relate to how they intend to incorporate a CLAS standard, or it may relate to how to improve retention rates. The change an agency identifies leads to a commitment to initiating and working towards a specific improvement in their clinic, or a change in a cultural norm that they practice. By supporting staff and leaders to adopt and implement process improvement through application of CLAS, the workforce is better equipped to integrate CLAS standards more effectively.

Intensive, customized technical assistance packages and services are available to promote the successful implementation of motivational interviewing with adaptations to match the staff and communities involved. The training may include introductory MI and/or advanced MI, which is then further supported through a custom-designed, culturally informed model of training. The training model is enriched by dialogue with the tribal authority staff or others associated with the facility who are familiar with how cultural adaptation and use of culturally specific tools could best be incorporated to enrich the learners’ experience. Additional follow-up sessions can strengthen people’s confidence and fidelity to the practice, as they receive individual coaching or sign on to recording and coding of interactions to model MI in practice. Organizationally, leadership training on MI implementation can further improve the prospects of successful results.

This full immersion program in clinical supervision offers a model of supervision and competency-based counselor skill development and prepares participants to be highly qualified clinical supervisors. The course has been customized to meet the diverse cultural and clinical needs of Tribal Clinical Supervisors. The curriculum includes live experiential training sessions and ongoing learning session opportunities, culminating in direct observation combined with individual coaching in specific supervision skills. Over a period of six months, tribal health staff across the four states of Alaska, Idaho, Oregon and Washington State receive training that, when completed, provides 30 NAADAC CE hours and meets all four states’ guidelines for being an approved Clinical Supervisor.